Topic 2 - Kinematics and Projectile Motion#

Kinematics is the study of the motion of a particle, such as its velocity and acceleration and the part it follows. Kinematics doesn’t deal with the forces that cause the motion, only the motion itself. The study of the cause of motion is known as dynamics which we will come back to in future Topics.

First we will look at the motion of particles in a straight line, with some focus on the particular case of acceleration due to gravity changing the velocity of the particle. We will then consider particle motion in two dimensions and then spend some time understanding this in the context of projectile motion where a particle is moving in two dimensions, one of which has gravity acting to cause acceleration in one dimension. Each of these builds on an understanding of the one that comes before it so you should be confident in your understanding and application of, for example, motion in one dimension before moving into two dimensions.

Note

In all of these cases we will be assuming that all acceleration is constant.

Motion in a straight line with constant acceleration.#

Imagine a particle moving in a straight line with a constant acceleration \(a\) for some time interval \(t\). During this time its velocity will change from some initial velocity \(v_0\) to a final velocity \(v\) while it travels some distance \(s\). What is really powerful here is that if you know any three of these quantities you can calculate the remaining two from a set of equations known as the kinematic equations (sometimes called SUVAT equations).

Summary table of variables

Variable |

Symbol |

SUVAT version |

|---|---|---|

Distance |

\(s\) |

\(s\) |

Initial velocity |

\(v_0\) |

\(u\) |

Final velocity |

\(v\) |

\(v\) |

Acceleration |

\(a\) |

\(a\) |

Time |

\(t\) |

\(t\) |

Kinematic (or SUVAT) equations#

As the velocity of the particle has changed from \(v_0\) to \(v\) in time \(t\), its acceleration is

As the acceleration is constant, the average velocity \(\left<v\right>\) is the average of the initial and final velocities:

But the average velocity is also defined as the time taken for a particle to travel some distance, giving

So we can set equations (3) and (4) equal to each other to give

We can substitute equation (2) into this to find

Next we can rearrange equation (2) to make \(t\) the subject of the equation to get

which can then be substituted into equation (5) to get

These derived equations are very important and are the set of kinematic equations used to describe the motion of any particle moving with uniform acceleration. I’ve summarised all of the equations into a single table below, as it’s more common for us to use the equations rather than derive them. However practicing algebra to derive them is an important skill.

Kinematic equation |

SUVAT format |

|

|---|---|---|

KE1 |

\(v = v_0+at\) |

\(v=u+at\) |

KE2 |

\(s = \left(\frac{v_0+v}{2}\right)t\) |

\(s = \left(\frac{u+v}{2}\right)t\) |

KE3 |

\(s = v_0t+\frac{1}{2}at^2\) |

\(s = ut+\frac{1}{2}at^2\) |

KE4 |

\(v^2 = v_0^2 + 2as\)^ |

\(v_2 = u^2 + 2as\) |

Worked Example 1

A particle is moving in a straight line from point \(O\) to point \(A\) with a constant acceleration \(a=2.0\text{ m s}^{-2}\). Its velocity at point \(A\) is \(30.0\text{ m s}^{-1}\) and it takes \(15.0\text{ s}\) to travel from \(O\) to \(A\). Find:

the particles velocity at point \(O\),

the distance \(OA\).

When solving problems of this type it is useful to list the known and desired quantities. Remember that for kinematic equations you need to know at least three variables to work out one or both of the remaining two.

\(a = 2.0\text{ m s}^{-2}\)

\(v = 30.0\text{ m s}^{-1}\)

\(t = 15.0\text{ s}\)

\(v_0 = \text{? (for part a)}\)

\(s = \text{? (for part b)}\)

Part a:

To find \(v_0\) we will use the kinematic equation KE1 and substitute in the known values:

So the velocity at point \(0\) is \(0.0\text{ m s}^{-1}\).

Part b:

To find the distance \(OA\) we use kinematic equation KE3:

So the distance \(OA\) is \(225\text{ m}\).

Note: it is possible to use kinematic equation KE2 instead. Try it to check that you get the same value of \(225\text{ m}\).

Worked Example 2 - Deceleration

A child on a skateboard is travelling up a hill. They experience a constant deceleration of magnitude \(2.0\text{ m s}^{-2}\). Given that their speed at the bottom of the hill was \(10.0\text{ m s}^{-1}\) determine how far up the hill they will travel before coming to a complete stop.

A deceleration of \(2.0\text{ m s}^{-2}\) is an acceleration of \(-2.0\text{ m s}^{-2}\).

Known and desired quantities are:

\(a = -2.0\text{ m s}^{-2}\)

\(v_0 = 10.0\text{ m s}^{-1}\)

\(v = 0.0\text{m s}^{-1}\) because the child has zero velocity at rest

\(s = \text{?}\)

Using kinematic equation KE4 gives

Vertical motion under gravity#

We are going to make the typical physics assumption that the effect of air resistance on a particle can be ignored, and with this assumption in place we are going to turn our attention to the case of a particle moving vertically with respect to the surface of the Earth.

We are also going to assume that the range of motion (i.e. the maximum height) is sufficiently small such that the acceleration due to gravity \(g\) is constant or uniform with a value of \(g=9.81\text{ m s}^{-2}\). This acceleration acts towards the centre of the Earth and as we tend to define upwards motion as positive then the acceleration due to gravity is negative because it acts in the opposite direction to the positive upwards.

It is perfectly acceptable to change the direction you define as positive, for example if all the motion is acting downwards then you can set down as positive. However when working with acceleration due to gravity and the surface of the Earth I find it more sensible to use upwards as positive so long as I ensure the signs of the variables are correct.

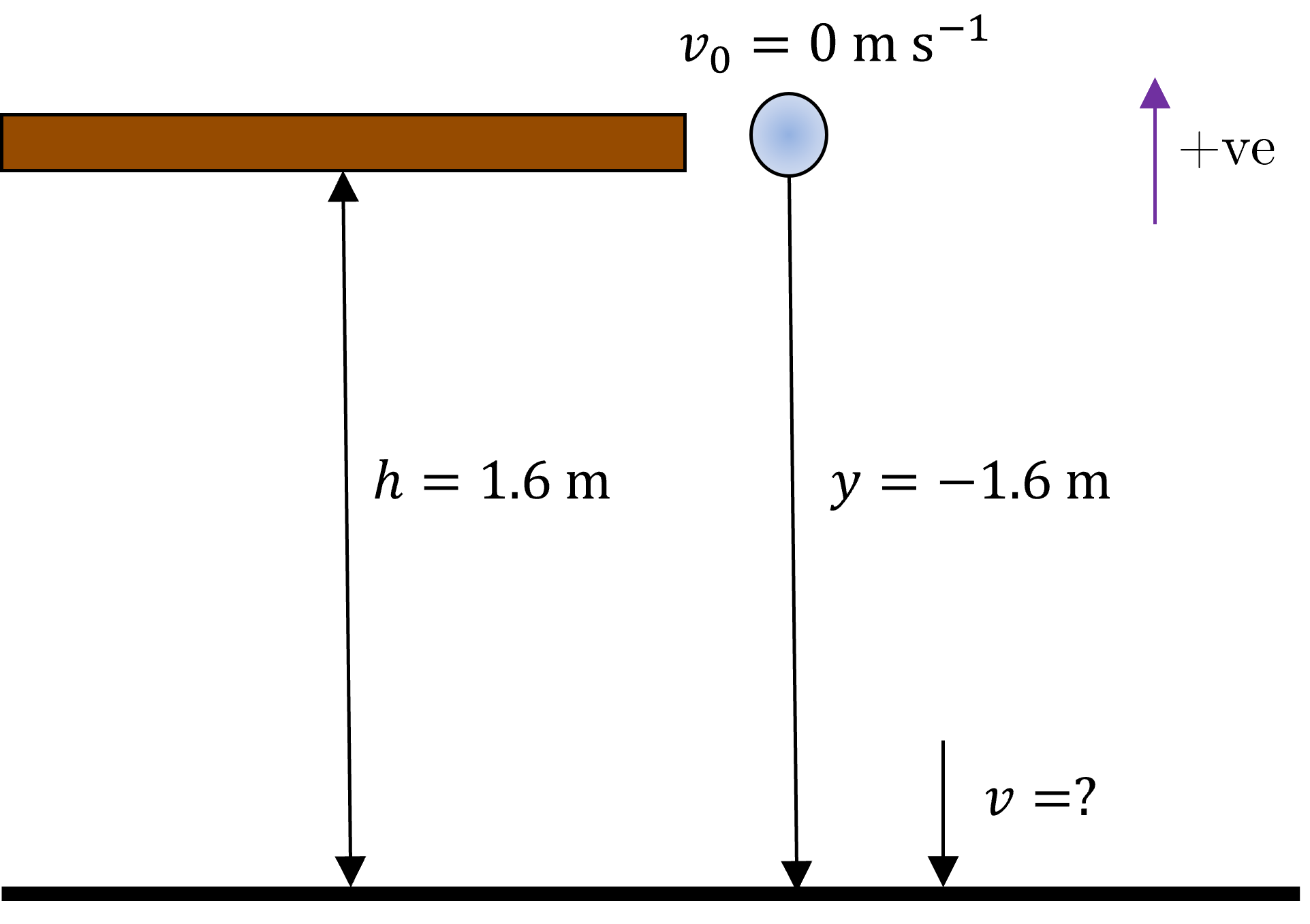

Worked Example 3 - Falling Marble

A marble falls from rest off a shelf which is \(1.6\text{ m }\) above the floor. Assuming that the marble falls vertically find:

the time it takes to reach the floor,

the speed of the marble as it hits the floor.

It always pays to draw a diagram, label all the variables and define which directions are positive. In this case motion only happens vertically so we only need to define positive in the vertical direction. Then list the variables you know and want in the same style as seen in previous worked examples.

Known and desired quantities are:

\(a = -g = -9.8\text{ m s}^{-2}\)

\(v_0 = 0.0\text{ m s}^{-1}\)

\(s = y = -1.6\text{ m}\) because the displacement from shelf to floor is in the negative direction

\(r = \text{?}\) (part 1)

\(v = \text{?}\) (part 2)

Part 1.

Using kinematic equation KE3

Part 2.

Using kinematic equation KE4

Worked Example 4 - Motion up and back down.

A particle \(P\) is projected vertically upwards from a point \(O\) with an initial speed of \(28\text{ m s}^{-1}\). Find:

the greatest height \(h\) above \(O\) reached by the particle

the total time before \(P\) returns to point \(O\)

the total distance travelled by the particle.

There is both upward and downward parts of the motion, so first start by deciding which direction is positive and specify all variables with the correct signs.

As acceleration is acting down and the particle first travels upwards it will be decelerated up to a maximum point, will be momentarily stationary, and will then begin to accelerate downwards due to gravity.

For parts 2 and 3 keep in mind the difference in definition between displacement and distance.

Part 1.

At the highest point the particle is momentarily stationary as the motion “switches” from an upwards to a downwards direction. So at this turning point the height is the maximum and the velocity is zero. Thus at this maximum point the known quantities are:

\(v_0 = 28.0\text{ m s}^{-1}\)

\(v = 0.0\text{ m s}^{-1}\)

\(a = g = -9.8\text{ m s}^{-2}\)

\(s = h = \text{?}\)

Using kinematic equation KE4 gives

Part 2.

When the particle returns to \(O\) its displacement \(s\) is zero. The known quantites are therefore:

\(s = 0.0\text{ m}\)

\(v_0 = 28.0\text{ m s}^{-1}\)

\(a = g = -9.8\text{ m s}^{-2}\)

\(t =\text{?}\)

Using kinematic equation KE3 gives

We could rearrange this and use the quadratic formula to find an expression for \(t\), but it is quicker to note that because \(s=0.0\) we can substitute this value in and then rearrange our equation into a simpler form.

Part 3.

The total distance travelled is the sum of the distance travellen upwards to the maximum height and the distance travelled from this point back to \(O\). This is twice the greatest height and therefore the total distance travelled is \(40.0\text{ m}\).

Projectile Motion#

Now that we’ve covered vertical motion under gravity, let’s dive into projectile motion. Projectile motion is what happens when you throw a ball or launch something at some angle into the air, and it then moves in both horizontal and vertical directions, which is more formally stated as the projectile has both horizontal and vertical components.

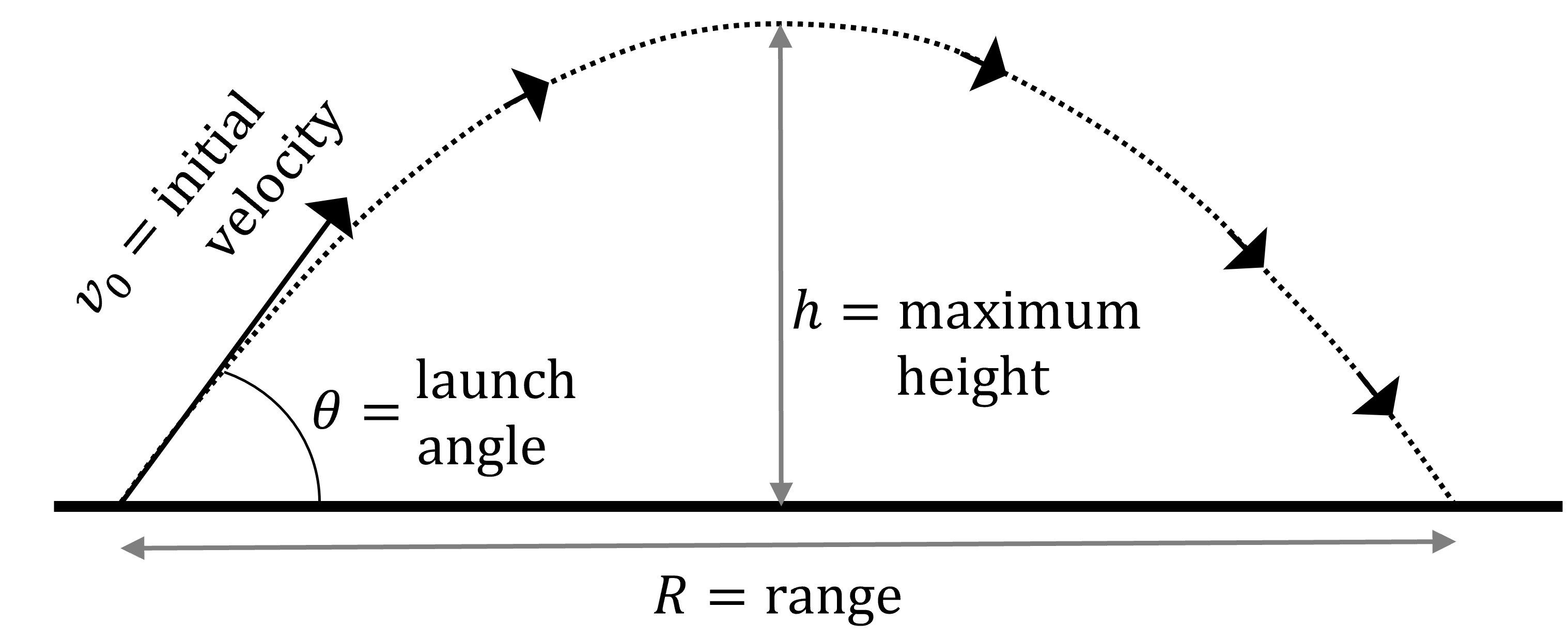

The key thing to know is that the horizontal and vertical components are independent of each other. This means gravity pulls the object down, affecting its vertical motion, while the horizontal motion stays constant. More specifically the vertical acceleration is \(g\) downwards whereas there is no horizontal acceleration (ignoring air resistance, as we normally do). This combination creates the curved path, or trajectory, that we see when something flies through the air - a diagram of this type of path is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2 The path of a projectile fired at some angle \(\theta\) to the horizontal. Two key parameters are labelled here, the maximum height \(h\) and range \(R\), and another key parameter the time of flight \(t_f\) is the time taken for the projectile to reach the landing point after it has been launched.#

Problems involving projectiles can be solved by considering the vertical and horizontal motions separately. As the acceleration is entirely vertical the projectile has no acceleration horizontally and so its horizontal velocity \(v_x\) is constant through the motion. Vertically, the motion can be defined using the kinematic equations we’ve already seen in the previous sections of this topic.

First we will consider projection at a positive (upward) angle to the horizontal to determine the range, maximum height and time of flight of a projectile. Then we shall look at the special case of a projectile being launched horizontally from some height (for example at the top of a cliff) as an example of the general case for any firing angle.

We’ll then end this topic by using vector notation to describe project motion and solve some problems using this approach.

Firing at an angle to the horizontal#

Look back at Fig. 2 which shows that projectile is fired with some initial velocity \(v_0\) at some angle \(\theta\) to the horizontal. We can resolve the initial velocity into two components, one in the \(x\) direction (\(v_{x,0}\)) and the other in the \(y\) direction (\(v_{y,0}\)). Using trigonometry we can state that

Time of Flight#

The time of flight \(t_f\) is the total time the projectile is in the air. To determine this, consider the vertical motion. At the peak of its trajectory, the vertical component of the velocity becomes zero. The projectile takes equal time to ascend to the peak and descend back to the ground.

The time to reach the peak can be found using the equation:

At the peak, \(v_y = 0\), so:

where \(t_\text{peak}\) is the time taken for the projectile to reach the peak of the trajectory.

The total time of flight is twice this time (up and down):

Maximum Height#

The maximum height \(h\) is the highest point the projectile reaches in its trajectory. This can be calculated using the vertical component of the motion. At the maximum height, the vertical velocity is zero.

Using the equation:

At the peak, \(v_y = 0\), so:

Range#

The range \(R\) is the horizontal distance the projectile travels before returning to the same vertical level from which it was launched. The range can be found by using the horizontal component of the initial velocity and the total time of flight.

The horizontal displacement is given by:

Substituting \(v_{0x} = v_0 \cos(\theta)\) and \(t_f = \frac{2 v_0 \sin(\theta)}{g}\) gives

Worked Example 5 - Projectile Motion 1

A particle is projected from point \(O\) on the ground with an initial speed of \(30.0\text{ m s}^{-1}\) at an angle of \(45^\circ\) up from the horizontal.

Find the maximum height the projectile reaches.

Find the range of the projectile once it lands on the ground.

You need to consider the horizontal and vertical motion separately.

Remember to specify which directions are positive, and ensure the signs of your known quantities are correct with respect to these directions.

Part 1.

The vertical speed when the particle reaches the maximum height is zero, so \(v_y=0\). Its initial speed is \(v_{y,0}=v_0\sin(45) = \frac{v_0}{\sqrt{2}}\). We can list the known and desired vertical quantities:

\(v_{0y} = \frac{v_0}{\sqrt{2}} \approx 21.2\)

\(v_y = 0\)

\(a_y = -g = -9.8\)

\(s = h = \text{?}\)

Using kinematic equation KE4 gives:

Substituting in the known quantities gives

Part 2.

To calculate the horizontal distance we need the horizontal velocity and the time of flight \(t_f\). Furthermore when the particle reaches the landing point the vertical displacement from its starting point is zero, which allows us to find \(t_f\):

\(v_{0y} = 21.2\) (from part 1)

\(s = h = 0\)

\(a = g = -9.8\text{ m s}^{-2}\)

\(t = t_f = \text{?}\)

Using kinematic equation KE3 gives

The right hand side of this factorised equation is only equal to the left hand side (i.e. zero) at two times: when \(t_f = 0\) and

As there is no horizontal acceleration the horizontal distance (i.e. the range \(R\)) is the horizontal velocity times the time of flight:

Special case - Horizontal projection#

A stone which is thrown horizontally with some initial velocity \(v_0\) from the top of a cliff will travel both horizontally (at a constant velocity) and will accelerate vertically until it reaches the ground or other landing point below.

The stone begins its journey at the highest point of the projectile path. At this highest point it has zero vertical velocity but is being accelerated by gravity directly downwards.

Worked Example 6 - Projectile Motion fired horizontally

A particle is projected horizontally with a speed of \(19.6\text{ m s}^{-1}\). Find the straight line distance \(L\) between the firing point and the position of the particle after \(1.5\text{ s}\).

For a particle fired horizontally the initial vertical component of velocity is zero, but all acceleration acts vertically due to gravity.

Firstly consider the horizontal component to find the horizontal distance from the starting point. As there is no horizontal acceleration we can state that:

Now the vertical motion. The known quantities are:

v_{0y} = 0

a = g = -9.8

t = 1.5 Using kinematic equation KE3 gives

where the minus sign tells us that the particle is below the firing point after 1.5 seconds.

The final straight line distance \(L\) can be found using Pythagoras’ theorem:

Projectile Motion with Different Landing and Firing Heights#

In many practical situations, the projectile lands at a height different from where it was fired. This section extends the earlier analysis to cover these cases.

Time of Flight with Different Heights#

When the landing height \(y_f\) differs from the initial height \(y_0\), the time of flight \(t_f\) cannot be assumed to be symmetric (i.e., it is not simply twice the time to reach the peak). Instead, we must account for the difference in height using the vertical motion equation.

Recall the vertical displacement equation:

To find the time of flight \(t_f\), set \(y(t_f) = y_f\):

Rearranging this, we obtain a quadratic equation in \(t_f\):

This equation can be solved using the quadratic formula:

Simplifying, we get:

Here, you take the positive root since time cannot be negative:

This is the general expression for the time of flight when the projectile lands at a different height.

Maximum Height#

The maximum height \(h\) reached by the projectile remains calculated the same way as in the standard case, because it only depends on the initial vertical velocity and gravity:

Range with Different Heights#

The range \(R\) can be found by first determining the time of flight \(t_f\) from the formula derived above, and then using the horizontal motion equation:

Where:

Thus:

This equation gives the horizontal distance travelled by the projectile when it lands at a different height.

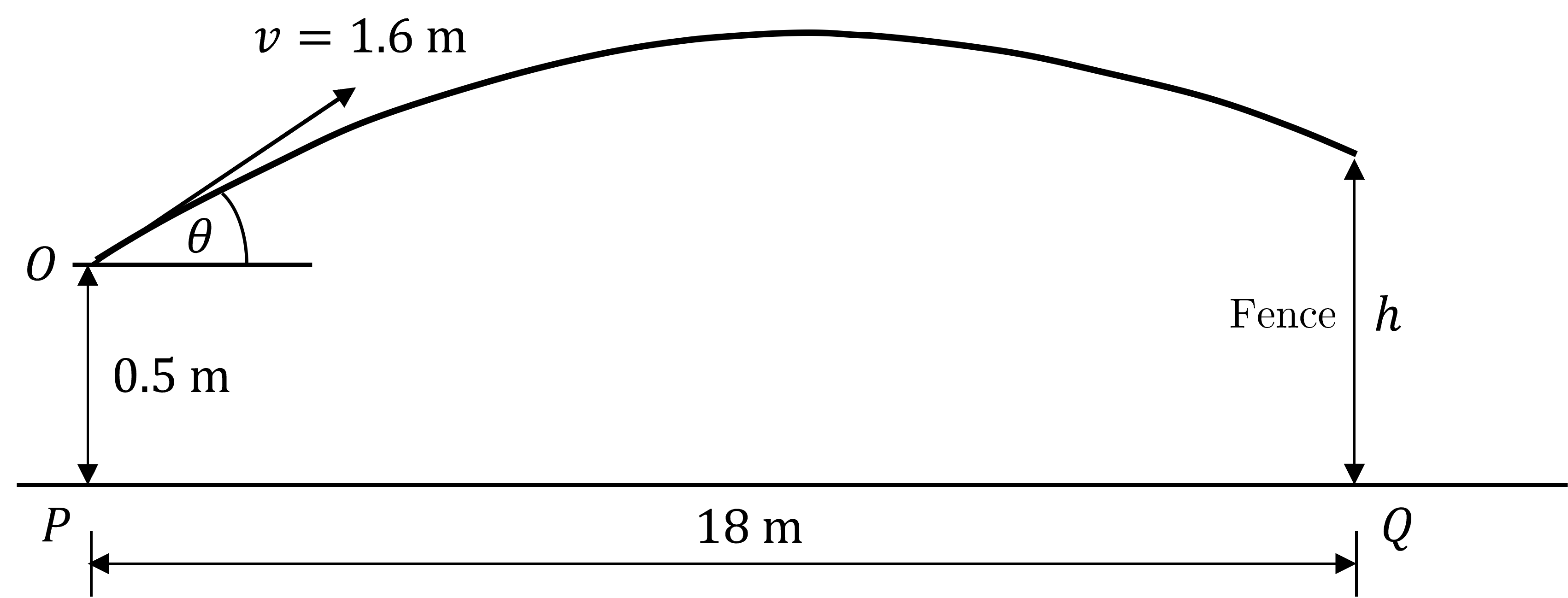

Worked Example 7 - Projectile landing at different height to firing height

A student hits a ball at an angle of \(\tan^{-1}\left(\frac{3}{4}\right)\) to the horizontal from a point \(O\) which is \(0.5\text{ m}\) above the ground. The initial speed of the ball is \(15.0\text{ m s}^{-1}\). The ball just clears a fence which is a horizontal distance of \(18\text{ m}\) from the student. By modelling the ball as a projectile find:

the time taken for the ball to reach the fence and,

the height of the fence.

A diagram here helps to ensure you are defining positive and negative distances correctly, with respect to the origin. In the figure below the origin is the firing point, meaning any distance below it will be negative.

The horizontal speed and distance \(PQ\) so the time taken to reach the top of the fence can be found.

The horizontal speed is \(15\cos\theta = 15.0\times \frac{4}{5} = 12.0\text{ m s}^{-1}\). Since the horizontal distance is \(18.0\text{ m}\) the time is

Next let the height of the fence be \(h\). At the moment when the ball just clears the fence it is \(\left(h-0.5\right)\) higher that its starting point. Known quantities for vertical motion are:

\(v_{0y} = 15.0\sin\theta = 15.0\times\frac{3}{5} = 9.0\text{ m s}^{-1}\)

\(t = 1.5\text{ s}\)

\(a = g = 09.8\text{ m s}^{-2}\)

\(s = (h-5) = ?\)

Using kinematic equation KE3

Summary of Differences from the Standard Case#

Time of Flight: Unlike the standard case, where \(t_f = \frac{2v_{0y}}{g}\), the time of flight here must be calculated using the quadratic equation when \(y_f \neq y_0\).

Range: The range is still \(R = v_{0x} \times t_f\), but \(t_f\) now comes from the adjusted formula, making the range dependent on the difference in height.

Maximum Height: The formula for maximum height remains unchanged, as it depends solely on the initial vertical velocity and gravity, not the landing height.