Topic 5 - Circular Motion#

Angular acceleration and forces#

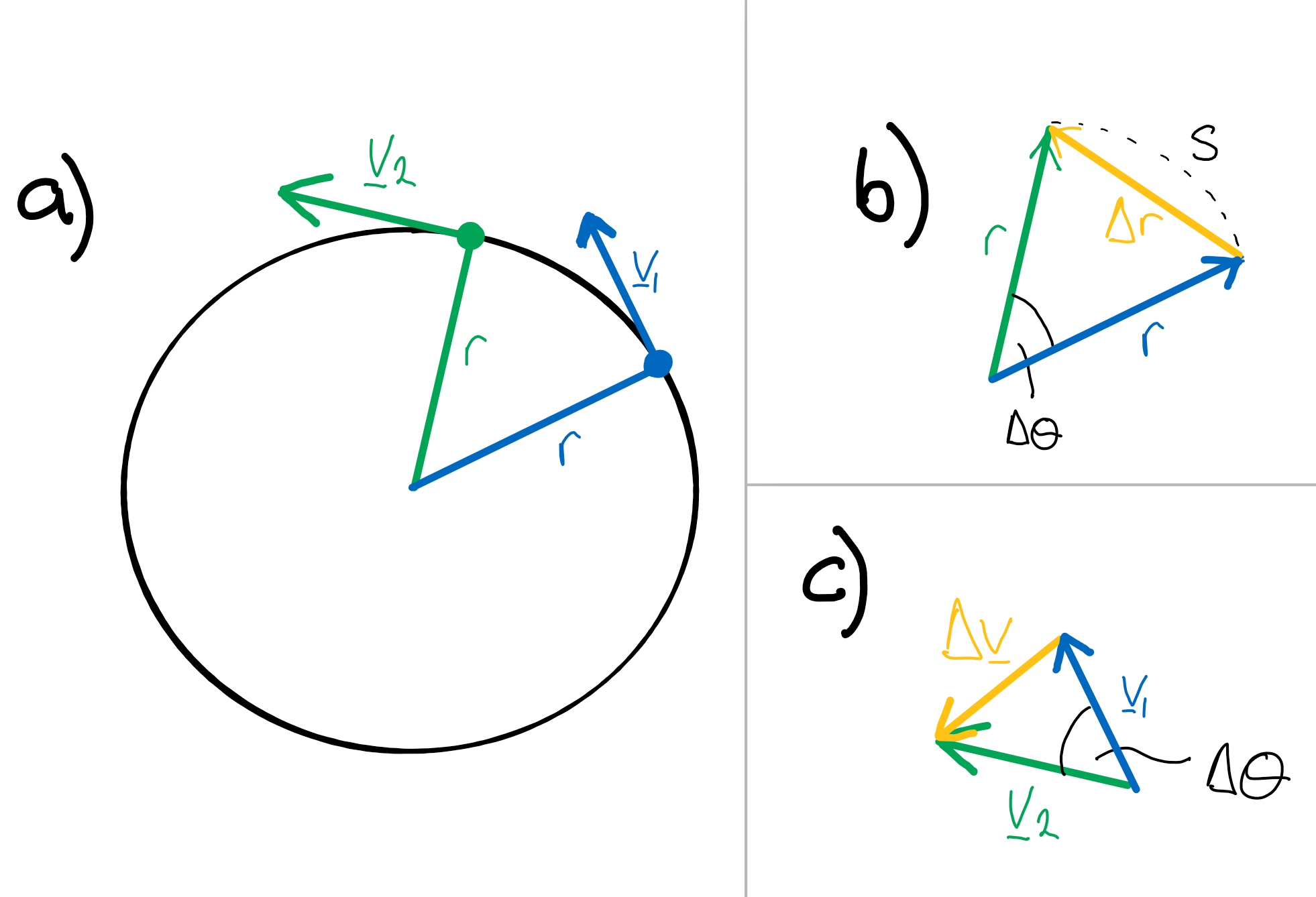

We are all aware by now that acceleration is a vector, so when we are dealing with circular and rotational systems we need to be mindful that the acceleration will be constantly changing even if the rotational speed remains constant. This is because the direction of the velocity vector is constantly changing around the circular path. This is shown in part a of Fig. 10 where we are imagining a particle moving in a circular path of radius \(r\) with some constant rotational speed and no external forces acting on the system.

Fig. 10 a) Two velocity vectors at different points of the circular path. The magnitudes of the vectors are the same but the direction differ. b) The arc length between these two point is approximated by the straight line distance \(\Delta r\) when the angle between the points \(\Delta \theta\) is small. c) The angle between the two velocity vectors is also \(\Delta\theta\) and the line between the end points of these two velocity vectors is itself a vector \(\Delta v\).#

In Fig. 10a there are two velocity vectors labelled, \(\textbf{v}_1\) and \(\textbf{v}_2\) for two specific point on the path. These two vectors have the same magnitude (\(|\textbf{v}_1| = |\textbf{v}_2| = v_t\), where \(v_t\) is the tangential velocity) but differ in their direction. We will make use of these vector arrows shortly.

Part b of the figure shows the arc length \(s\) that the body travels along between the two specific points. If we take the limiting case that the time difference \(\Delta t\) between these two points is sufficiently small then the arc length is approximated by the straight line \(\Delta r\) and therefore

Let us now return to the velocity vectors. We can construct a vector triangle using the two velocity vectors to find the change vector \(\Delta \textbf{v}\). If we now recall that the velocity vectors are at a tangent to the radius vector to the body we can see that the two triangles constructed in Fig. 10b and c are similar triangles - the radii and velocities both subtend the same angle \(\Delta\theta\). Thus

This acceleration is always directed towards the centre of the circle and is perpendicular to the velocity. It is the acceleration that acts to change the direction so that the body stays on a circular path - if this acceleration were to disappear the body would then move in a straight line along the tangent to the curve at the point where the acceleration stopped, and with a velocity equal to the tangential velocity. This expression for \(a\) is probably familiar to you from you pre-University courses but now you have one way in which you can derive it from scratch. There are other methods you could use that are in different textbooks (each book seems to have their own method) but I personally find this the most simple and delightful.

But wait! We have already seen that an acceleration is the result of a force acting on the body in question. This allows us to define a centripetal force \(F_r\) that acts to keep the body on a circular path, starting from Newton’s Second law for a constant mass system,

So we have shown that there needs to be this centripetal force acting to cause the centripetal acceleration. But what exactly is this force? The answer depends very much on the system that you are concerned with. For a planet orbiting a star the centripetal force acting on the planet is gravity, whereas in the Bohr model of the atom the electrostatic force acts to keep the electron orbiting the nucleus.

Ball on a string - two examples#

Imagine we have a ball of mass \(m\) on a string of length \(L\) We are going to look at two different cases of the ball making a circular path parallel to the horizontal plane and the conical pendulum.

Horizontal plane#

The technical terminology may suggest this is a complicated case, but it is in fact the simplest we can work with. Imagine that the ball is being swung around fast enough that the string is perfectly horizontal. In this case we can ignore the external force of gravity because it is perpendicular to the centripetal force and therefore does not contribute to the net force.

This means that our centripetal force is simply the tension in the string \(T\) and so

Conical Pendulum#

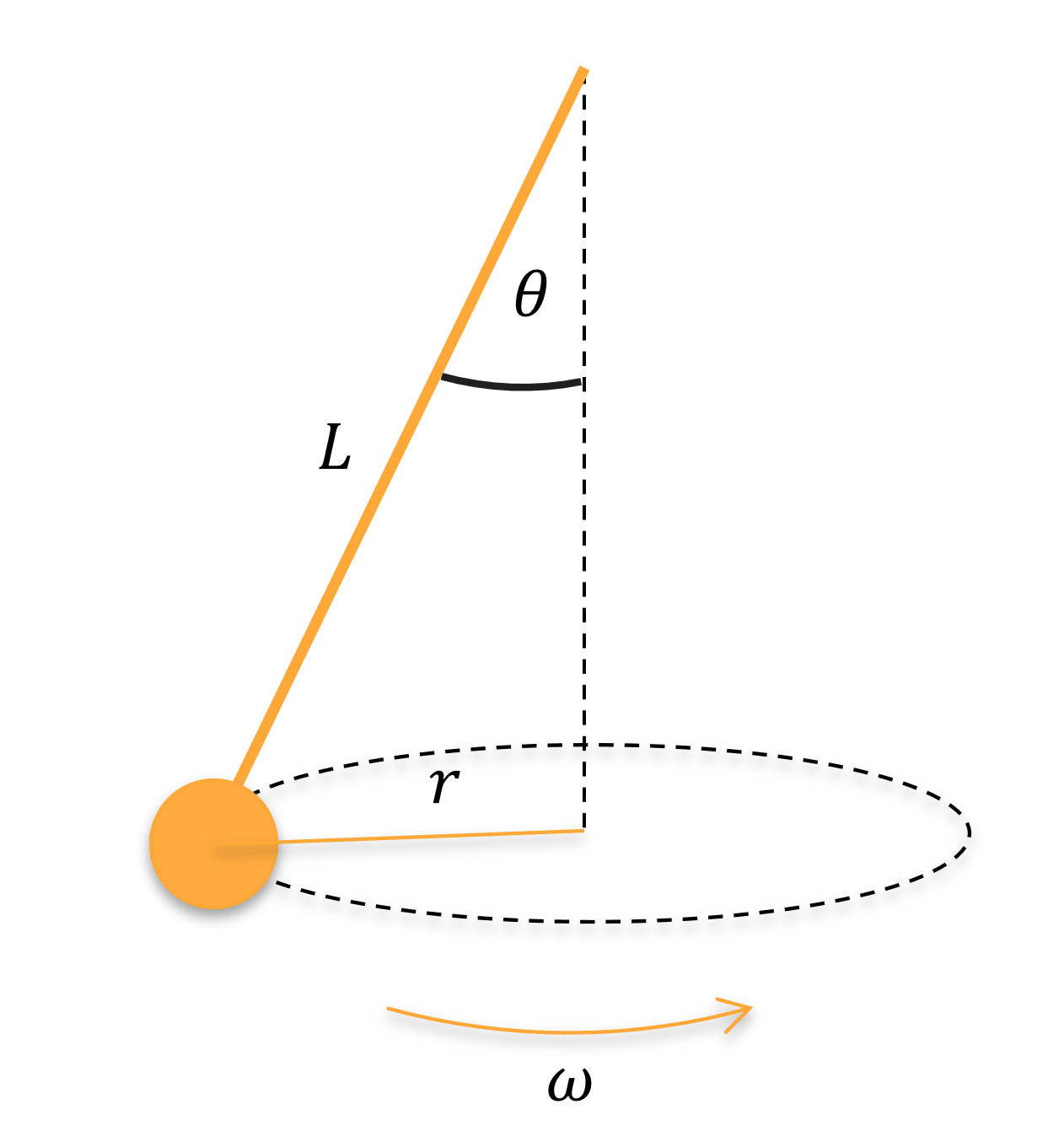

Fig. 11 Schematic of a conical pendulum of string length \(L\). The mass traces a circular path of radius \(r\) in the horizontal plane but the pivot point is above the horizontal plane.#

The conical pendulum is another system in which the circular path of the swinging ball is in the horizontal plane but now the string is no longer parallel to the horizontal. A schematic diagram is shown in Fig. 11 and the angular velocity \(\omega = \frac{v}{r}\). Note that the radius of the circular path \(r\) is not equal to the length of the string \(L\), which is an easy and common mistake to make.

The conical pendulum has both horizontal and vertical components so we need to resolve the component forces if we want to solve any problems involving this system. Firstly we will consider the horizontal forces. The centripetal force is due to the horizontal component of the tension, i.e.

whereas the vertical components require us to have zero net vertical force beause the mass is not accelerating vertically. We can express this as

We can combine these two expressions to find

Friction round a corner - an example#

Another physical and everyday example that we can analyse is the maximum cornering speed of a vehicle. In this case the physical process causing the centripetal force is the friction between the vehicle tyre and the road. This friction force \(f_s\) is proportional to the normal force and as we are, perhaps counterintuitively, dealing with the coefficient of static friction we can state the force due to friction as

where \(\mu_s\) is the coefficient of static friction. The maximum cornering speed occurs when the centripetal force is equal to the static frictional force so we can find the maximum velocity of a vehicle before it will skid out

Non-uniform circular motion#

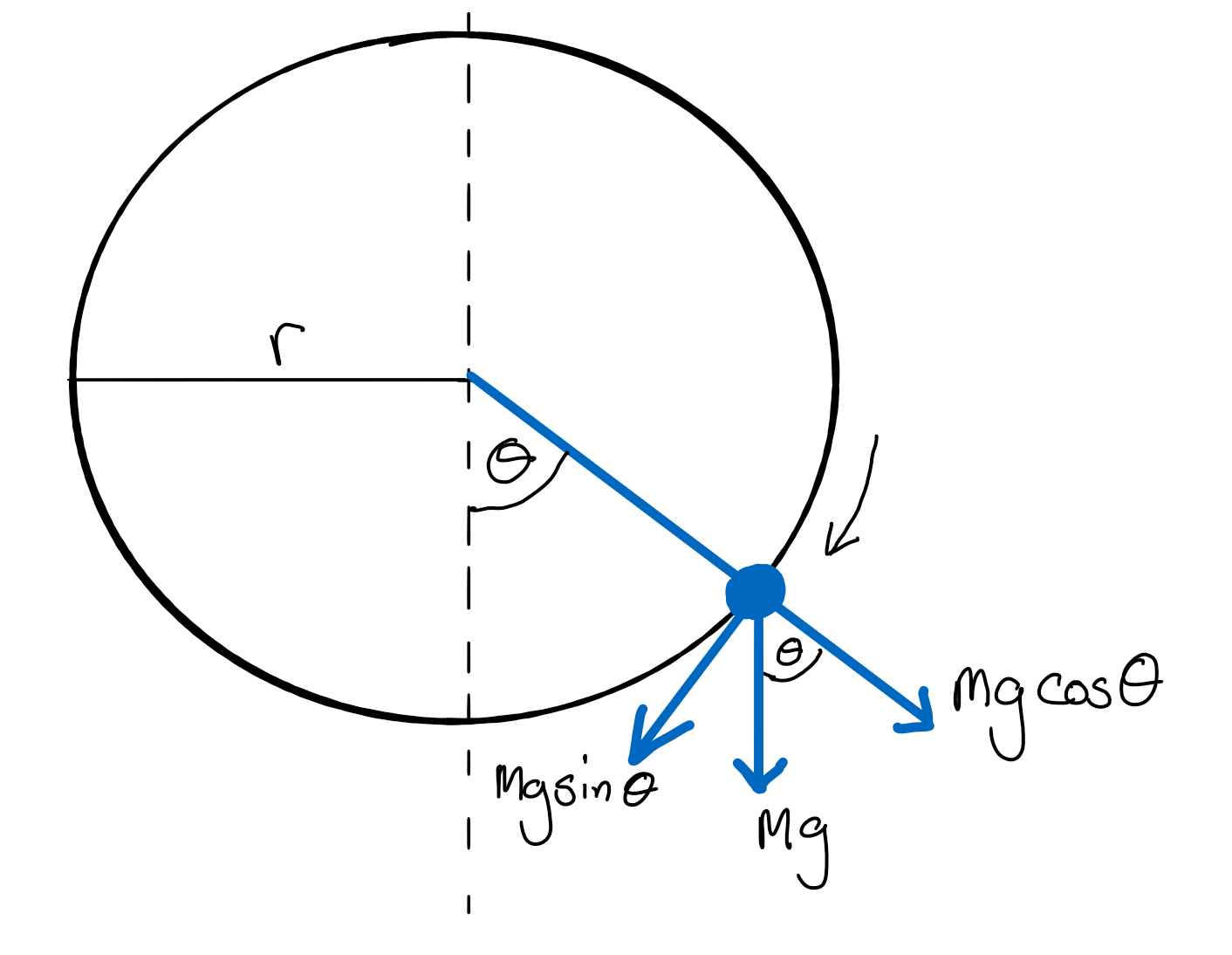

In all of the examples we have examined previously the circular path traced out by the moving body has been parallel to the horizontal, and consequently the tangential (and therefore angular) velocity is constant. Now we are going to rethink our ball on a string experiment but this time we will swing the ball around such that the circular path is in the vertical plane only. In this setup the tangential velocity is not constant because the components of force due to gravity vary depending on the position in the circular path. Take a look at Fig. 12 showing a ball of mass \(m\) moving in a clockwise circle of radius \(r\) in the vertical plane.

Fig. 12 Schematic of a circular path in the vertical plane. Gravity acts on the rotating mass and the total gravitational force always acts down but the component acting parallel to the tangent of the path varies as a function of \(\theta\) around the circular path.#

Once again we need to consider the two components of the different forces acting on our system. However if we were to jump straight in a try to define this in terms of Cartesian coordinates (i.e. the typical \((x,y)\) system) then we immediately see the model is going to be complicated. The ball is moving in a circular path so if we make a change in \(x\) then there will also be a change in \(y\), but it is much easier if we can have two orthogonal parameters that vary independently.

This is where we can make use of the coordinate systems you have seen in your maths courses. Instead of expressing the position of the ball with an \((x,y)\) coordinate we can instead use the radius and angle of the ball, \((r,\theta)\). The unit vectors of these two parameters are perpendicular and so meet our orthogonality requirement, and we can also change one without changing the other. Awesome.

So now we want to consider the radial and tangential components of the forces acting on our system.

Let us start with the tangential (i.e. the ones acting in the \(\hat{\mathbf{\theta}}\) direction) components. We have the tangential component of gravity which we can equate, using Newton’s Second Law, to the net tangential force.

where \(a_t\) is the tangential acceleration.

Next we move onto considering the radial forces. We know that the total sum of the forces is the centripetal force which in this case equals the tension in the string \(T\) minus the radial component of gravity. The minus here is because the component from gravity is acting outwards and our centripetal force and the tension are acting inwards. This gives

You may be wondering why I have chosen to define the angle \(\theta\) with \(\theta=0\) at the bottom of the circle rather than zero being at the top. This is so that when \(\theta=0\) equation (21) becomes

which gives the correct opposing directions of the tension and gravity when the ball is at the bottom of the path. This is what we expect because gravity is acting downward whereas tension is acting completely upwards. If I were to define \(\theta=0\) at the top of the path then I would need to change the minus sign in equation (21) to a plus, but personally I find this means the physical interpretation of what the equation is describing becomes less self evident.

Worked Example 5.1

The blade of a circular saw is initally rotating at 7000 revolutions per minutes (rpm). The motor is the switched off and the blade slows to a complete stop in 8.0 seconds. What is the average angular acceleration?

If you’re still not comfortable with rotational kinematics then think of the linear equivalent.

And remember to work in SI units!

First we convert the initial angular velocity \(\omega_i\) from rpm to \textbf{radians} per second

The final angular velocity \(\omega_f=0\) and hence the average angular acceleration is

Worked Example 5.2

An automobile accelerates uniformly from 0 to 80 km/h in 6.0 seconds. The wheels have a radius of \(0.3\) m. What is the angular acceleration of the wheels, assuming they roll without slipping?

“Accelerates uniformly” means that the acceleration is constant.

The translational acceleration of the automobile is

remembering that you need to convert everything into SI units.\ The angular acceleration is related to the translation acceleration as

Worked Example 5.3

A large centrifuge at the Sandia National Laboratory is used for testing the behaviour of components of rockets, satellites and re-entry vehicles when subjected to high accelerations. The centrifuge has an arm length of 8.8 m and has a maximum rotation speed of 175 revolutions per minute. What is the tangential speed at the end of this arm, and what is the centripetal acceleration?

Nothing too complicated required here, just remember to convert to the right units.

First we convert \(175\text{ rpm} = \dfrac{175}{60} = 18\) revolutions per second, and thus the angular velocity is

The tangential speed at the end of the centrifuge arm is

and the centripetal acceleration is

which is almost \(300\,\,g\)!

Worked Example 5.4

Calculate the following centripetal accelerations as multiples of \(g\):

acceleration toward the Earth’ axis of rotation of a person standing at a \(45^{\circ}\) latitude.

acceleration of the moon towards the Earth.

acceleration of an electron moving around a proton with a tangential velocity of \(2\times10^6 \text{ m s}^{-1}\) in an orbit of radius \(0.5\overset{\circ}{A}\). Note, this is the ground state in the Bohr atomic model for hydrogen.

acceleration of a point on the rim of a bicycle wheel of diameter 66 cm if the bicycle is travelling along at 11 m s\(^{-1}\)

All four of these questions use the same basic formulae, just in different ways. A good starting point is to write the variables that you know, and see which equations have the right combination of unknown and desired variables.

1 The centripetal acceleration is the same as that of a person standing on the edge of a disc with radius \(r=R_{\text{Earth}}\cos\theta\) where \(\theta = 45^{\circ}\). This gives

2 The moon takes one month to orbit the Earth, so the time period is \(T = 30\times24\times60\times60=2592000\) seconds and a corresponding frequency of \(f=\frac{1}{T} = 3.86\times10^{-7}\). We take the Earth-Moon distance to be \(R_{\text{Earth-Moon}}=3.7\times10^{8}\text{ m}\). The acceleration is thus

3 This time we have the tangential velocity rather than the time period given in the previous two questions, which means

4