Topic 4 - Energy, Power and Momentum#

Energy is, at best, strange. As a concept it perhaps the most far-reaching in terms of applicability but is also one of the most difficult to define completely and succinctly. We explain it in terms of different units, with different equations and models, and try to use general defining statements such as energy being something we ‘pay’ in order to get things done. One particular attempt that I like is from A. P. French (1971) who claimed that

Energy is the universal currency that exists in apparently countless denominations; and physical processes represent a conversion from one denomination to another.

But none of these truly define what energy is. But thankfully this should not be regarded as an issue; Kramer once reflected in a symposium that

The most important and most fruitful concepts are those to which it is impossible to attach a well-defined meaning.

Having a well-defined meaning of energy is less important and useful compared to how we consider the transformation of energy. We cannot define energy in general but we can and will make heavy use of the fact that it is conserved, a statement that we will accept at face value.[1]

If we take the rather fluffy statement that energy is is paid to do something, then we can define the property “work” that quantifies how this paid energy transforms our system from one state to another. For the purposes of this course we will only be considering dynamical states, i.e. motion.

Work, Energy and Power#

Work#

In the last topic we discussed how the change in the dynamics, i.e. the acceleration of a body is a result of an applied force. We are of course making the assumption here that the mass remains constant meaning we are making use of the special case of Newton’s Second Law.

Let us expand on this idea. We have already established that an applied force will give rise to an acceleration, but we can consider the work done when applying this force over a certain distance.

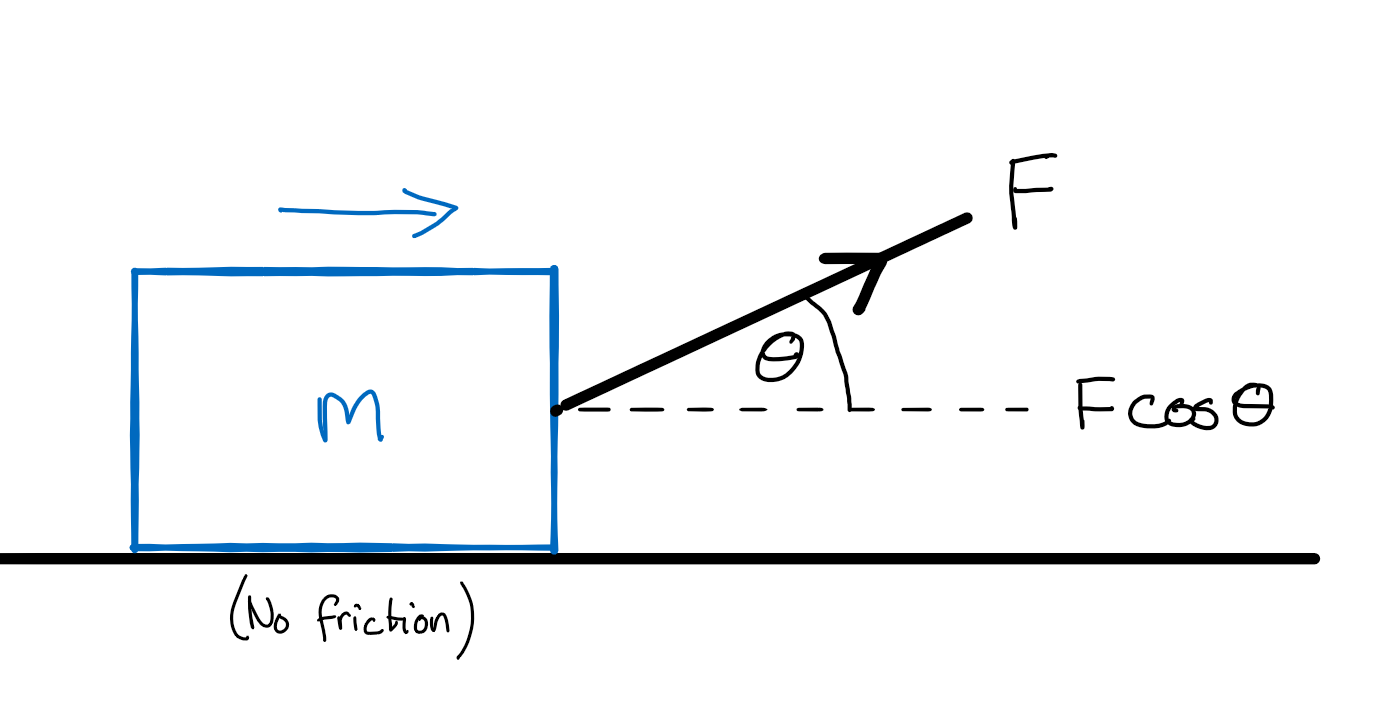

The system we will first consider is a box being pulled along the ground with some constant force \(\textbf{F}\), as shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7 A box dragged horizontally across a floor by a force applied at some angle \(\theta\) to the horizontal. Assume there is no friction between the box and the floor.#

Assume there is no friction between the box and the ground. The work done \(W\) in moving this box some distance \(x\) is

We need to define some terms here. \(F_x\) is the horiztonal component of the force \(\textbf{F}\), \(\theta\) is the angle between the horizontal and the direction of \(\textbf{F}\), and \(\textbf{x}\) is the distance vector with magnitude \(x\) and points in the horizontal direction (i.e. along the unit vector \(\hat{\textbf{x}}\), such that \(\textbf{x}=x\hat{\textbf{x}}\)). The last line of these equations is known as the dot product or scalar product of two vectors. I am going to assume you know these as they are or will be taught in your mathematics courses.

This is the very special case in which the force remains constant over the distance \(x\) so a logical next step would be to consider what happens if the force is not constant but instead is some function of \(x\)? This is possible but involves splitting the distance up into very small steps and then adding them all together. You may not have seen integration yet in your maths course, so if not just skip over this paragraph until you’re familiar with this very useful mathematical technique.

If we make the displacements really small we can state that the total work done in moving the box from \(x_1\) to \(x_2\) is

Worked Example 4.1 - Work done

A packing case is pushed \(5.0\text{ m}\) across a smooth floor by a horizontal force of constant magnitude \(30.0\text {N}\). Find the work done on the box by the applied force.

The force is constant so we can use \(W = F_xx\).

Using the constant force expression, noting that the force \(F_x\) is all in the direction of motion (i.e. there is no vertical component to the applied force)

Worked Example 4.2 - Work done against gravity

An angler catches a fish of mass \(1.5\text{ kg}\). Find the work they do against gravity in raising the fish \(4.0\text{ m}\) from the surface of the water to the pier, assuming they wind their line at a constant speed.

Constant speed means the system is not accelerating. Think how acceleration and forces are linked.

Model the fish as a particle(!) moving vertically. As the speed is constant there is no acceleration, and therefore no net acceleration.

Using Newton’s Second Law we can state:

Work done by gravity \(=F_yy\) where I’ve changed to \(y\) instead of \(x\) as the motion is vertical, and so

Worked Example 4.3 - Work done against friction

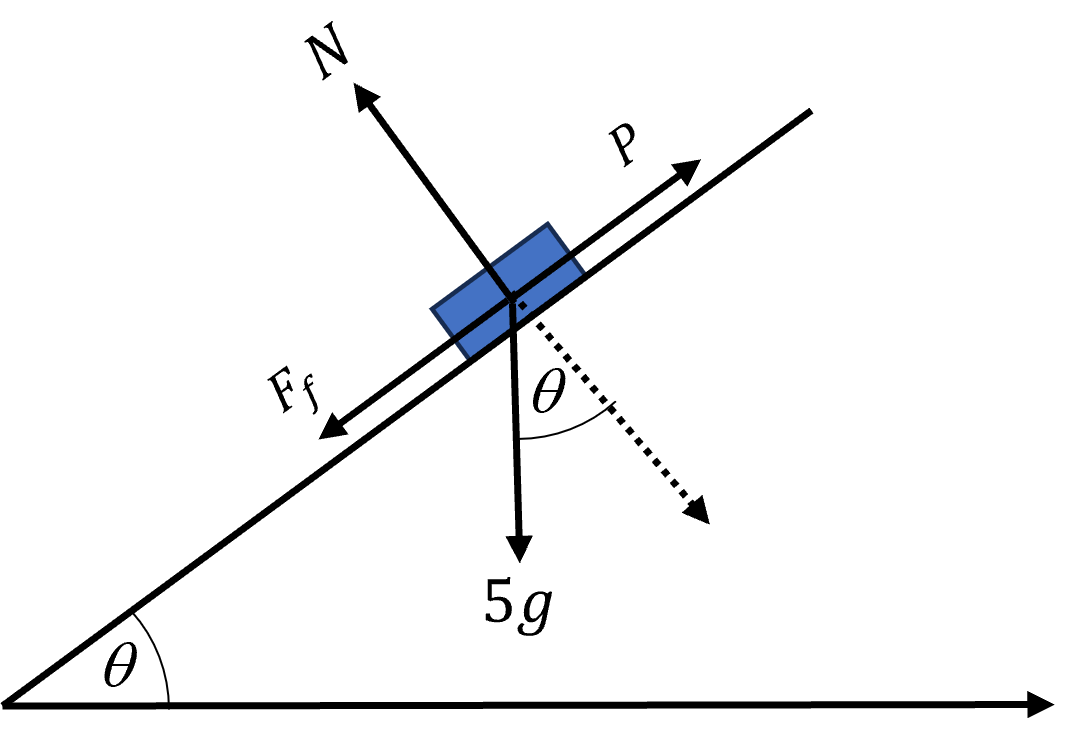

A box of mass \(5.0\text{kg}\) is pulled a distance of \(24.0\text{ m}\) up a rough plane at a constant speed. This plane is inclined at \(40^\circ\) above the horizontal. If the coefficient of friction between the box and the plane is \(\mu=0.25\) find:

the work done against friction, and

the work done against gravity.

When a particle is pulled up a rough inclined plane at a constant speed work must be done against the frictional force acting on the particle as well as against gravity, though these forces are acting in different directions so a force diagram will be a very sensible place to start.

In the diagram above \(P\) is the pulling force, \(F_f\) the frictional force, and \(N\) the normal force perpendicular to the surface.

Part 1

For this part it is easier to consider forces and motion parallel and/or perpendicular to the plane of the surface.

As there is no motion perpendicular to the plane:

Using \(F=\mu N\) with \(\mu=\frac{1}{4}\) gives

The box moves a distance \(s=24.0\text{ m}\) (anti)parallel to the direction of the friction force, and so the work done against friction is:

Part 2

For this part we are considering gravity so it is easier to consider forces / motion / distances in terms of vertical and horizontal components.

Worked Example 4.4 - Work done for force at an angle to direction of motion

A packing case is pulled across a smooth horizontal floor by a force of magnitude \(20.0\text{ N}\) inclined at \(30^\circ\) to the horizontal. Find the work done by the force in moving the packing case a distance of \(10.0\text{ m}\).

We’ve already seen this drawn in Fig. 7

First we need to find the horizontal component of the force:

The work done is the horizontal component of force times the horizontal distance travelled:

Kinetic Energy#

The kinetic energy of a particle is the energy it possesses by virtue of its motion. Consider a particle of mass \(m\) moving horizontally through a vacuum under some applied horizontal force \(F\). This force accelerates the particle from an initial velocity \(v_i\) to a final velocity \(v_f\) after travelling a distance \(s\).

Combining the work done equation (\(W=Fs\)) with Newton’s Second Law (\(F=ma\)) gives

We can rearrange Kinematic Equation 4 in terms of acceleration, i.e.:

and substituting this into our new expression for the work done gives:

and if the particle is starting from rest then the work done is

where K.E. is the kinetic energy of the particle, and is equal to the work done in changing the velocity of the particle.

If more than one force acts on the particle then the force used to calculate the work done (and hence the kinetic energy of the particle) is the resultant force in the direction of motion.

Worked Example 4.5 - Kinetic energy of a pulled object

A particle of mass \(2.0\text{ kg}\) is being pulled across a smooth horizontal surface by a horizontal force. The force does \(24.0\text{ J}\) of work in increasing the particle’s velocity from \(v_i=5.0\text{ m s}^{-1}\) to \(v_f\). Find the value of \(v_f\).

The change in kinetic energy of a system is equal to the work done on the system.

The work-energy theorem states that:

Potential Energy#

The potential energy, PE, of a system is the energy it possess by virtue of its position within a gravitational field, or less formally its height. If a particle of mass \(m\) is raised by some height \(h\) then the work done in moving the particle is equal to

In other words, the work done in moving a particle vertically upwards is equal to the increase in potential energy of the particle. If the particle is lowered then its potential energy is decreased by an amount equal to the work done by the particle.

Some care is needed here. The change in potential energy is proportional to the change in height, so a more precise restatement of the above equation would be

where the change in height \(\Delta h = h_\text{final} - h_\text{initial}\).

Worked Example 4.6 - Lifting a parcel

A parcel of mass \(5.0\text{ kg}\) is raised vertically through a distance of \(7.0\text{ m}\). Find the increase in potential energy.

The change in potential energy is related to the change in height, so you should define a zero / starting / reference point.

Defining the initial starting point as \(h_i=0\) the change in potential energy in lifting the parcel to height \(h_f\) is

Worked Example 4.7 - Child going down a slide

A child of mass \(25.0\text{ kg}\) slides \(4.0\text{ m}\) down a smooth playground slide inclined at an angle of \(35^\circ\) to the horizontal. Calculate the potential energy lost by the child.

Change in potential energy is related to the change in height, not necessarily the total distance travelled (unless all motion is vertical).

Taking the bottom of the slide to be the zero level for P.E., the vertical distance travelled by the child is \(4.0\sin 30^\circ\) and so the potential energy change is:

where the minus sign indicates that potential energy has been lost (more accurately it has been converted into kinetic energy as the child moves faster).

Conservation of energy#

Consider a particle that is falling freely under gravity and without air resistance. The only force acting on the particle is its weight.

If the particle increases its speed from an initial speed \(v_i\) to a final speed \(v_f\) after descending some height \(h\) then

the work done by gravity \(W = mgh\) = change in PE

the change in kinetic energy = final KE - initial KE = \(\frac{1}{2}mv_f^2 - \frac{1}{2}mv_i^2\) = work done

As the work done is the same in both of these statements it follows that

This means that the change in potential energy = - change in kinetic energy. The minus sign here means that if the potential energy increases, kinetic energy must decrease and vice versa. This allows us to make the statement that, in the absence of any external forces doing work on the system:

A particle’s total energy is constant.

Worked Example 4.8 - Using kinetic and potential energy for sliding down a ramp

A particle of mass \(2.0\text{ kg}\) is released from rest and slides down a smooth plane inclined at \(\sin^{-1}\left(\frac{3}{5}\right)\) to the horizontal.

Find the distance travelled when the particle has increased its velocity to \(5.0\text{ m s}^{-1}\).

Care needs to be taken with the different distances involved. Potential energy is defined by a change in height (vertical), whereas kinetic energy corresponds to motion in any direction.

Let the distance travelled down the slope be \(x\). The decrease in height is therefore

Next we find the decrease in P.E.:

and the increase in K.E.:

as the initial velocity is zero. Since the decrease in P.E. = increase in K.E. we can equate these two expressions to find

Power#

Power is defined as the rate of work done to perform a task (such as moving an object). Mathematically this is given by \(P=\frac{W}{t}\) and power has the units of watts where 1 watt is 1 joule per second.

This is often combined with the definition for work done under a force applied \(F\) over a given distance \(s\), meaning that power could be expressed as

Notice that the distance and time terms can easily be combined into the velocity, as \(v = \frac{d}{t}\) meaning that for moving objects the power per second is:

This approach is more typical as power is more useful in terms of the amount of work done per unit second rather than needing to know the total distance travelled and time taken to travel this distance.

Worked Example 4.9 - Power from distance

A force of magnitude \(1500\text{ N}\) pulls a truck up a slope at a constant speed of \(6\text{ m s}^{-1}\). Given that the force acts parallel to the direction of motion find the power of the system pulling the truck.

You need to consider the distance travelled per unit second, as we do not know (or need to know) the total distance and duration of force applied

The work done per second is the force times the distance travelled in one second, so

The power is the rate of doing work, i.e. the work done per second, and so

Worked Example 4.10 - Power from velocity

A car of mass \(1000\text{ kg}\) is travelling along a level road against a constant resistance of magnitude \(475\text{ N}\). The engine of the car is working at $4\text{ kW}. Calculate:

the acceleration when the car is travelling at $5\text{ m s}^{-1}, and

the maximum speed of the car.

The car is accelerating, which gives a link to the net force. We have one force from the engine (linked to power) and the resistive force so a resultant force can be found.

A maximum speed means it is no longer accelerating.

Part 1

First we need to covert into \(W\) from \(kW\), so \(4\text{ kW} = 4000\text{ W}\).

Using \(F=ma\) where \(F\) is the resultant force gives:

Part 2

When the car is travelling at its maximum speed there will be no acceleration so the resultant force in the direction of motion is zero.

Hence \(F = 457\text{ N}\) and so

Momentum#

Suppose a particle of mass \(m\) moving in a straight line with contant acceleration increases its speed from \(v_i\) to \(v_f\) in time \(t\). Then its acceleration can be found using:

Applying this to Newton’s Second Law gives

This quantity of \(\text{mass}\times\text{velocity}\) is called the momentum of the particle, and is a vector quantity because it depends on the particle’s velocity.

Worked Example 4.11 - Momentum of single particle

A particle of mass \(5\text{ kg}\) is at rest on a smooth horizontal surface. A horizontal force of magnitude \(4\text{ N}\) acts on the particle for 6 seconds. Find the final speed of the particle using the principles of momentum.

Smooth means no friction, and the particle only moves horizontally meaning weight and normal force balance, so the only force we need to be worried about is the pushing horizontal force.

Using

Conservation of momentum.#

One of the most far reaching and useful property of momentum is that is a conserved property. Once again the formal proof of Noether’s Theorem shows that conservation of momentum is necessary due to the differentiable symmetry of space, but this theorem is not necessary to learn for this course. We can however make some use of Newton’s Laws to demonstrate that momentum is indeed conserved.

If we have an isolated system of two bodies where the net force of body A acting on body B is \(\textbf{F}_{AB}\) and that of body B on A is \(\textbf{F}_{BA}\) then we can make use of Newtons Second Law to state

These two statements can be combined by making use of Newton’s Third Law:

The total momentum of this system of two bodies is \(\textbf{P}=\textbf{p}_A+\textbf{p}_B\). This means that equation (13) can be rewritten as

which is only true if \(\textbf{P}\) is constant.

Key point

The total momentum of a system is constant if the vector sum of the external forces acting on the system is zero.

Collisions in 1D#

Knowing the definition of momentum and the conservation of momentum law is all well and good but being able to apply it is much more useful. For the remainder of this chapter we are going to look at some very idealised cases in one dimension and see how the conservation of momentum can be used and how it does (or does not) apply in conjunction with the conservation of energy. As in all cases where we are only considering the idealised case there is quite a departure from the real world applications, but as ever a good foundation in the principles and dealing with idealised cases allows you to modify and expand for every more complicated and realistic situations.

The two types of idealised collisions we will explore are the perfectly elastic case and the perfectly inelastic case. It is worth stressing here that whilst kinetic energy may or may not be conserved for the different cases we will examine, the total momentum is always conserved in the absence of any external forces. A common mistake in dealing with these types of systems is assuming that kinetic energy is equal before and after the collision.

Perfectly elastic collisions#

An elastic collision is defined as a collision where the kinetic energy of the system is the same before and after the collision. In other words, the total kinetic energy is conserved.

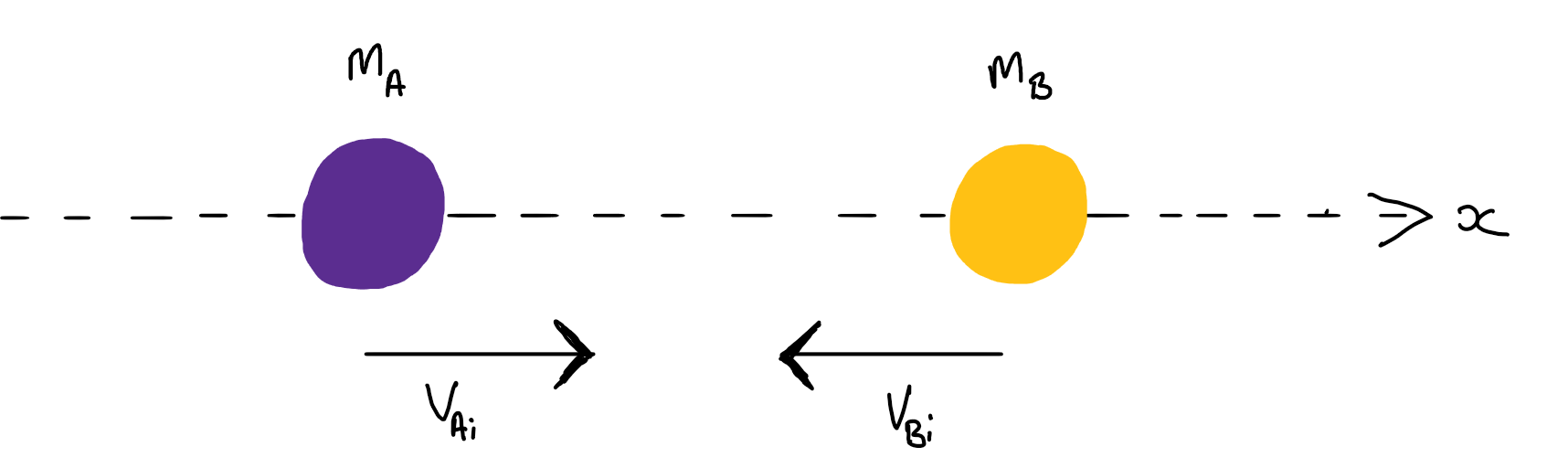

Imagine we have two objects \(A\) and \(B\) with masses \(m_A\) and \(m_B\) respectively, and are travelling along the \(x\)-axis with initial velocities \(\textbf{v}_{Ai}\) and \(\textbf{v}_{Bi}\) respectively. In the event that they collide the bodies then have final velocities \(\textbf{v}_{Af}\) and \(\textbf{v}_{Bf}\) respectively. We know that the total momentum is conserved which allows us to state,

Note that the momenta and velocities in the above expressions are vectors, as they should be. It does allow us to readily expand this into a two and three dimensional system but for the sake of easier visualisation I am going to split out the magnitude and directions of the vectors. For our one dimensional case this is trivial as the direction is either positive or negative along the \(x\)-axis - anything other than this and it would not be a one dimensional system. This gives

where a negative velocity means the body is travelling in the negative \(x\) direction.

We are going to consider the four different types of system that can be constructed when we start to give different directions and relative velocities to the bodies \(A\) and \(B\). In each of the cases we are going to focus on calculating the final velocities assuming that we know the masses and initial velocities.

Moving towards each other initially

Fig. 8 Two masses \(m_1\) and \(m_2\) moving towards each other along the \(x\) axis with different velocities.#

We will be making use of equation (14) but if we are wanting to derive expressions for both of the final velocities then this equation alone is not enough. In order to solve for two variables we need two equations. We need to make use of the physics involved in an elastic collision and note that the total kinetic energy is also conserved. This means that

With some fairly straightforward algebra and making use of the completing the square method we find

Now we take the rearranged form of equation (14), namely \(m_A\left(v_{Ai}-v_{Af}\right)=m_B\left(v_{Bf}-v_{Bi}\right)\) and substitute this into equation (15) above. This then simplifies to

Taking this equation and substituting for \(v_{Bf}\) into equation (14) gives

where \(M\) is the total mass \(m_A + m_B\).

You can follow similar steps to find the following expression for \(v_{Bf}\)

Sense Check

This is a perfect opportunity for me to emphasise one of the most important yet often underrated problem solving techiques in physics. The idea behind this sense check process is to take the results you have from your derivations, in our case equations (17) and (18), and apply some specific conditions to see whether the model in the equation represents what you would expect to happen in the real world.

Take the first example of imposing the condition that \(m_A = m_B = m\). With this condition in mind our two equations become

which in words would be described as an exchange of velocities. This is much more apparent if we think about a snooker or pool situation and we say that one of the balls is initially at rest. Once the moving ball of identical mass hits the stationary ball then the initially moving one stops completely and the initially stationary ball moves off with the inital velocity of the impacting ball.

Another condition we can think about is assuming that one of the masses is significantly larger than the other. For the interest of making the interpretation easier we are going to impose the condition that \(v_{Bi}=0\), although the actual conceptual understanding we draw from this still applies if object \(B\) is initially moving.

If \(m_A\ll m_B\) then our two equations for the final velocities become

Putting this into English we would say that the little mass \(A\) bounces off the much larger mass \(B\) and goes backwards with the same velocity (remember this is an elastic collision) whereas mass \(B\) just stays still. This checks out with what we would expect for throwing a small mass at a much larger mass.

Taking the reverse condition of \(m_A\gg m_B\) we find

Translating this into the real world experience we find that the much heavier and initially moving mass just keeps going at the same speed after the collision whereas the much smaller and initially stationary mass flies off at twice the speed of the incoming large mass. Again this checks out with our expectations based on our experience of reality.

Moving away from each other at the start

The objects simply do not collide.

Nevertheless if you were to plug the values into equation (14) you would still get an `answer’ for the variable you were solving for, and generally you end up with the rather obvious results of \(v_{Ai}=v_{Af}\) and \(v_{Bi}=v_{Bf}\).

Moving in positive \(x\) direction, \(v_{Ai}> v_{Bi}\)

Fig. 9 Two masses \(m_1\) and \(m_2\) moving towards each other in the same direction along the \(x\) axis with different velocities. The velocity of the mass in front is less than that of the mass behind. Without this condition the masses will not collide.#

You will be pleased to know that we have already done this derivation in the first case (“Moving towards each other initially”).

We have determined, from simply looking at the system, that a collision will indeed take place so we can use the exact same result as above. The only difference here is that when we get to the stage of putting in the values for the initial velocities they will all be the same sign - in the diagram above they will all be positive but it is also applicable to the bodies moving in the negative \(x\) direction but will require \(v_{Ai} < v_{Bi}\) for a collision to occur.

Moving in positive \(x\) direction, \(v_{Ai} < v_{Bi}\)

The objects simply do not collide. Mass \(B\) is ahead and has a larger velocity, so mass \(A\) never catches up with \(B\).

Perfectly inelastic collisions#

We now move away from the elastic condition that has by definition the requirement that the total kinetic energy in conserved. In an inelastic collision the total kinetic energy is not conserved which means some of the initial energy is ‘lost’ during the collision. Although we could consider systems where a collision occurs and the two bodies move apart (i.e. considering the elastic case but with energy loss) this turns out to be somewhat complicated as we need to quantify the amount of energy lost. This is beyond what we need to do for this course so instead we will focus our attention on a specific case of inelastic collisions in which the two initially separate bodies stick together at and after the collision, and thus move as one body.

Compared to the elastic case this situation is much easier to derive. We start again by stating the conservation of momentum equation (14) but we now have a single mass \(M\) moving with velocity \(v_f\) after the collision. Thus

The final velocity is the sum of the weighted initial velocities, where the weighting is determined by what fraction of the total mass each body represents. I am going to give you three sense check conditions that you should think about and see whether the modified version of equation (19) describes what you would expect to happen in the real world.

\(m_A = m_B = m\)

\(m_A \ll m_B\)

\(m_A \gg m_B\)

Worked Example 4.12 - Collision against a fixed object

The collision between an empty car (mass \(m\) and initial velocity \(v_i\)) and a solid barrier lasts \(0.120\text{ s}\).

Derive an expression for the average force exerted on the wall, if the velocity of the car after the collision is \(v_f\).

If the mass of the car is \(1700\text{ kg}\) and the initial and final velocities are \(13.6\text{ m s}^{-1}\) and \(-1.3\text{ m s}^{-1}\) respectively, calculate the average force on the barrier.

There are lots of parameters involved here. It can help to list the ones you know (mass, velocity and time), the ones you’re after (force), and identify any intermediate ones you may need to calculate (in this case, momentum).

1 With the \(x\) axis along the direction of the initial motion, the change in momentum is

2 Plugging in the numbers will give the force on the car by the wall

From Newton’s 3rd law the forces on the car and barrier are of equal magnitudes and opposite directions. Therefore the average force on the barrier is \(\left<F\right> = +2.11\times10^{5}\text{ N}\)

Worked Example 4.13 - Perfectly elastic collision

A SuperBall, made of a rubberlike plastic, is thrown against a smooth, hard wall. The ball strikes the wall from a perpendicular direction with speed \(v\). Assuming that the collision is perfectly elastic find:

the speed of the ball after the collision.

the change in momentum of the ball.

Pay close attention to the words used in the question. In this case whether you’re asked for a scalar or a vector quantity.

1 We assume that the collision is perfectly elastic, in part because the wall is much more massive than the ball and as such the reaction force of the ball on the wall will not impart any appreciable velocity on the wall. Therefore the velocity of the ball after the is simply \(-v\).

2 If the \(x\) axis is definited in the direction of the initial motion, then the momentum before the collision is \(p_{\text{before}} = mv\) and the momentum after is \(p_{\text{after}} = -mv\). Hence the change in momentum is \(\Delta p = p_{\text{after}} - p_{\text{before}} = -2mv\).

The wall has an equal and opposite momentum change of \(+2mv\) so that the total momentum is conserved. The wall can `acquire’ this momentum without acquiring any appreciable velocity because its mass is so large, and it is attached to an even more massive building.

Worked Example 4.14 - Perfectly elastic collision of extended objects

An empty railway carriage of mass \(m_1 = 20\) metric tons rolling on a straight track at \(v_{1i}=5.0\text{ m s}^{-1}\) collides with a loaded stationary carriage of mass \(m_2 = 65\) metric tons. Assuming the cars bounce off each other elastically, find the velocities after the collision.

The expressions needed have already been derived above. The fact these are extended masses (carriages) rather than small coloured dots makes no difference.

Starting from equations (17) and (18) and setting \(v_{2i}=0\) we can use the values in the question to find

I have left the mass units as tons because the fractions in the above equations are a ratio of masses so the overall term is dimensionless. Always worth checking, but if in doubt convert to SI units to be on the safe side.

Worked Example 4.15 - Perfectly inelastic collision of extended objects

Suppose that the carriages in Worked Example 4.14 coupled during the collision and remain locked together.

What is the velocity of the coupled carriages after the collision?

How much energy is lost during the collision?

“Coupled together” means the collision is inelastic.

1 We have a completely inelastic collision here, so from the conservation of momentum

2 The energy lost \(E\) is the difference between the final and initial kinetic energies