Topic 3 - Forces#

“Axiomata Sive Leges Motus’’, or Axioms or Laws of Motion#

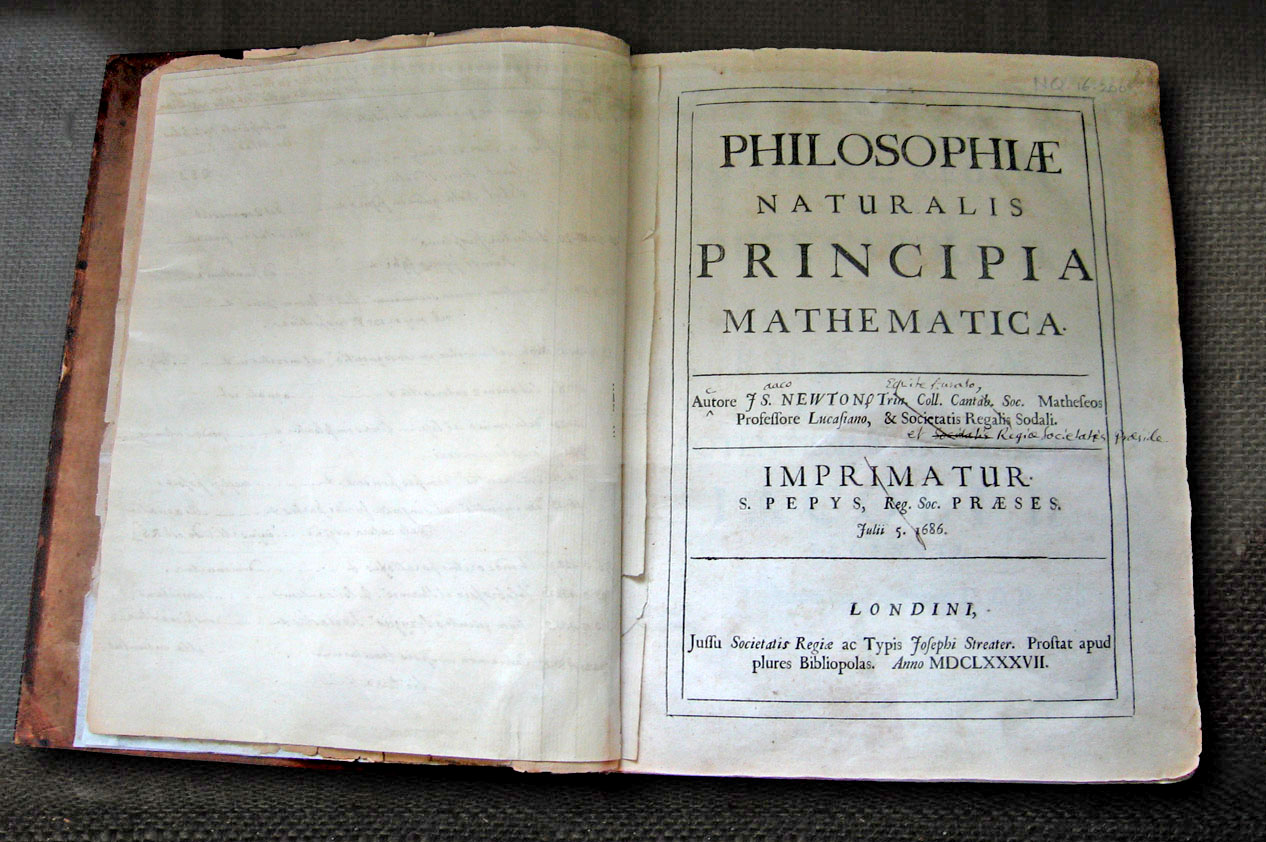

Fig. 3 Newton’s own copy of his Principia, with hand-written corrections for the second edition, in the Wren Library at Trinity College, Cambridge.#

In this chapter we are going to look at some of the work that Isaac Newton developed way back in the 17th century. Unfortunately we are not going to dabble in his obsession with alchemy[1] or finding the Philosopher’s Stone, but instead will concern ourselves with a particular section of the “Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica’’ published in 1687. In this work Newton defines three laws of motion that set the foundation for the field of classical mechanics which you will study in more depth next year.

You will already have seen these three laws of motion but there are some concepts or details that are often overlooked in pre-University courses so firstly we will review the three laws in turn before applying them to some representative examples.

I will forewarn you now that I’m going to make a point of including the original Latin of the three laws. There is some educational benefit to this, I assure you, but it is also a historical thing that usually gets lots of eyerolls from the audience. I fully intend to honour this tradition until I retire.

First Law#

Corpus omne perseverare in statu suo quiescendi vel movendi uniformiter in directum, nisi quatenus a viribus impressis cogitur statum illum mutare.

Every body persists in its state of being at rest or of moving uniformly straight forward, except insofar as it is compelled to change its state by force impressed.

The key point that I want to emphasise with this law is a subtle one but thinking about it now will help in the future when you start thinking about special relativity. Newton makes reference to the ‘state’ of the body. This state could be at rest or a constant motion straight forward but in all cases they are simply specifics of this general ‘state’. This state is the velocity of the body which means we can rephrase the First Law as

A body acted on by no net force moves with constant velocity.

The zero velocity case is simply a unique value in an almost infinite number of possible velocities. Sometimes it is convenient to make use of the zero velocity case, particularly when you start thinking about different frames of reference.

Second Law#

Mutationem motus proportionalem esse vi motrici impressae, et fieri secundum lineam rectam qua vis illa imprimitur.

The alteration of motion is ever proportional to the motive force impress’d; and is made in the direction of the right line in which that force is impress’d.

This is by far the Law that is most frequently stated incorrectly. Or perhaps more accurately it is that the law taught to you in schools in a special case of a simplified version of the actual statement the Newton made. You will have heard people saying that the second law is simply \(F=ma\) however let us look at the original statement to see what information is missing when we look between the original and this simple-yet-incomplete definition.

What I hope you notice is that the original statement contains two key parts, conveniently separated by a semi colon. In the first part we have that the alteration of motion, or acceleration, is proportional to the applied force. This is all good and gels with our simple statement that \(F\propto a\), where the mass \(m\) is our constant of proportionality.

The information in the original definition that is lacking in our \(F=ma\) statement is that regarding the directions of the applied forces and the resulting acceleration.

When we want to combine information about the magnitude and direction of properties you should always think about vectors.

By combining the two components of the original statement for the Second Law we can give a more general statement of the law in mathematical form, namely that

Have you spotted the ‘error’ yet?

I was being rather picky with my choice of words right after the Latin and translation text. I said that the version taught is schools is both simplified and a special case. We have taken care of the simplification by including the directions by way of vectors but the special case element needs to be addressed.

Let us look back at equation (8). I was quite correct to not change the mass into a vector, but what I have assumed is that the mass is constant. In fact I need to go back to the original statement of the Second Law and think more generally about the “alteration of motion” and consider a property that contains both the velocity and mass of the body. This is, of course, the momentum \((\textbf{p}=m\textbf{v})\) of the body.

If we now reformulate the Second Law using this concept of the momentum into an equation we find that

We can now check that this more general expression does reduce to the more familar form in equation (8) under special circumstances. Let us take equation (9) and apply the product rule

so in the special case that the mass remains constant the right hand term become zero and therefore we find that

but only when the mass is constant. You should try to rememorise Newton’s Second Law as the force applied to a body in a given time, also known as the impulse equals the rate of change of momentum of that body.

Third Law#

Actioni contrariam semper et aequalem esse reactionem: sive corporum duorum actiones in se mutuo semper esse aequales et in partes contrarias dirigi.

To every action there is always an equal and opposite reaction: or the forces of two bodies on each other are always equal and are directed in opposite directions.

I won’t spend as much time on this Law as there is not as much to critique, but again the key point to emphasise is that in the original statement is there is mention of the magnitude and the direction of the forces. We can neaten this up slightly by introducing our good friends the vectors. If we consider a body A that is exerting a force of magnitude \(F_{AB}\) onto body B then body B exerts a force of magnitude \(F_{BA}\) onto body A, and so we can state that

Summary of the three laws#

Key point

First Law: A body acted on by no net force moves with constant velocity (which may be zero).

Second Law: The general mathematical form is \(\textbf{F}=\dfrac{\mathrm{d}\textbf{p}}{\mathrm{d}t}\). This reduces to \(\textbf{F}=m\textbf{a}\) only in the case where the mass remains constant.

Third Law: If body A exerts a force on body B, then body B exerts a force on body A of the same magnitude but in the opposite direction, i.e. \(\textbf{F}_{AB} = -\textbf{F}_{BA}\)

Units of force#

All forces, regardless of their type or underlying physical cause, have units of Newtons. One Newton is equal to one kilogram meter per second squared \((\text{kg m s}^{-2})\).

Types of forces#

Below are four examples of types of force though you will come across more as you study different areas of physics. These four are chosen as they strongly relate to mechanics and will be discussed in more detail, in some cases simultaneouly where appropriate.

Weight#

All particles falling freely under gravity have the same acceleration, \(g\). This acceleration must be caused by a force acting on the particle, as required by Newton’s Second Law. This force is the weight of the particle and is equal to \(F_\text{weight} = mg\) where \(m\) is the mass of the particle.

Tension#

Imagine a particle of mass \(m\) hanging in equilibirum at the end of a string. As the particle is in equilibrium the weight \(mg\) acting downwards must be balanced by an equal and opposite force acting upwards (as per Newton’s Third Law). This upward force is the tension \(T\) in the string, and is a pulling force on the particle.

Worked Example 3.1

A small object is hanging in equilibrium at the end of a vertical string. Find:

the weight of the object if its mass is \(0.2\text{ kg}\).

the mass of the object if its weight is \(4.9\text{ N}\).

the tension in the string if the mass of the object is \(1.0\text{ kg}\).

the tension in the string if the weight of the object is \(5.0\text{ N}\).

Mass and weight are not the same, although they are related. Mass is an intrinsic property of the object whereas weight is a force acting on the mass due to gravity.

In these types of questions you can assume the system is on Earth, unless told otherwise!

The weight \(W = mg = 0.2\times9.8 = 1.9(6)\text{ N}\)

Rearranging the equation for weight gives \(m = \frac{W}{g} = \frac{4.9}{9.8} = 0.5\text{ kg}\).

The object is in equilibrium meaning the tension in the string (force upward) must equal that of the weight (force downward).

Therefore \(T = W = mg = 1\times 9.8 = 9.8\text{ N}\).The same argument applies as for part 3 of this question, so \(T = W = 5\text{ N}\).

Friction#

When an object is in contact with a rough surface and you try to push the object across said surface then a frictional force acts to oppose the pushing force. The frictional force acts parallel to the surface, and only when the surface is perfectly smooth does the frictional force equal zero.

We will revisit friction in more detail shortly, but first we need to better understand how to resolve forces to find the resultant force (or resultant forces in Cartesian components).

Resultant forces#

We have already seen in Topic 1 that we can add two vectors together to find a single resultant vector. As forces are vector quantities the same applies here - we can add multiple forces (in vector form) to get a single resultant force vector.

Suppose that two forces, \(\textbf{F}_1\) and \(\textbf{F}_2\) are acting on a particle. The resultant force \(\textbf{R} = \textbf{F}_1 + \textbf{F}_2\), and then from Newton’s Second Law we can state that the acceleration of this particle is:

Suppose that a third force \(\textbf{F}_3\) also acts on the particle. The resultant force is now the sum of these three forces, i.e. \(\textbf{R} = \textbf{F}_1 + \textbf{F}_2 + \textbf{F}_3\).

More generally the resultant force is the sum of all forces acting on the particle, which can be neatly written using summation notation as:

Worked Example 3.2

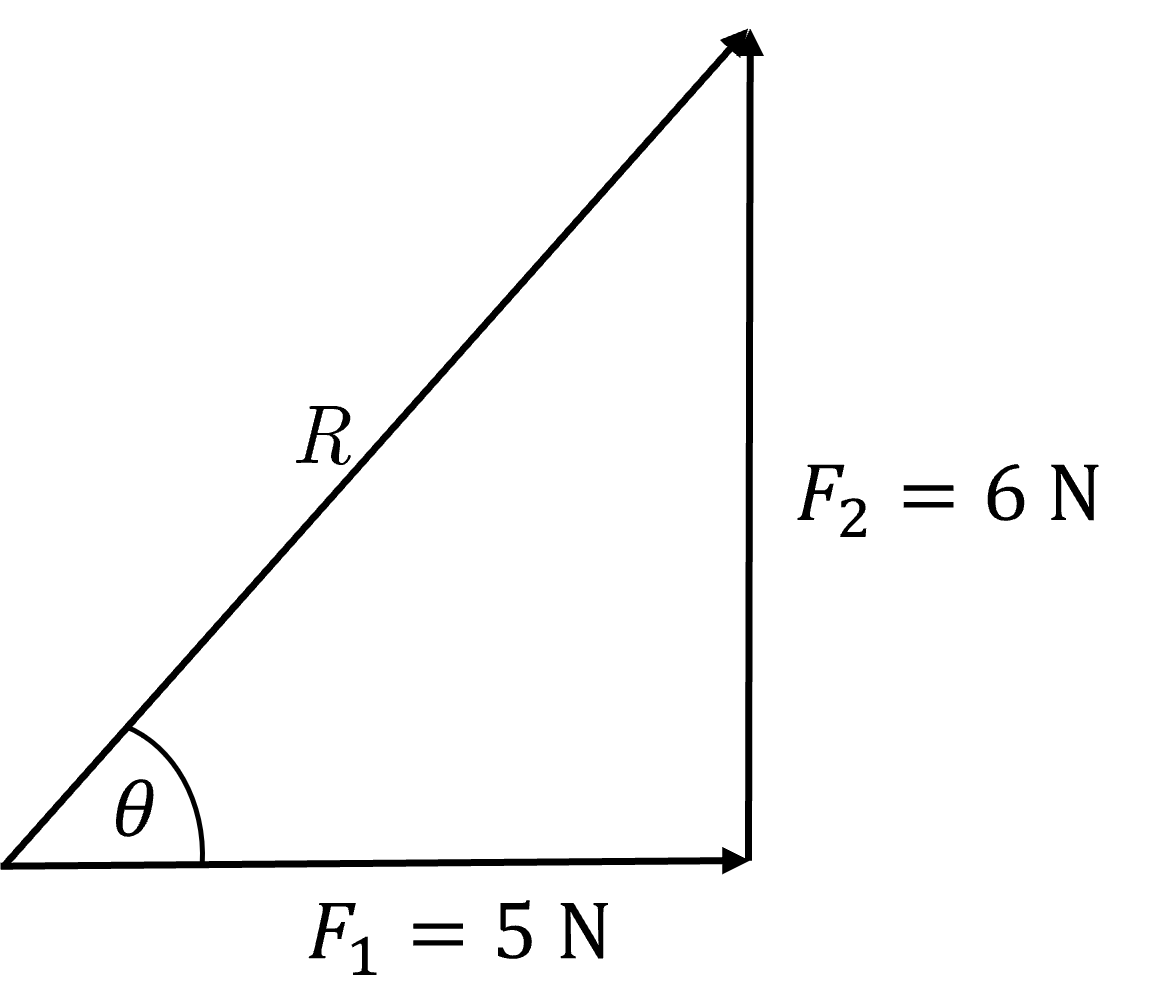

Two forces of magnitude \(5\text{ N}\) and \(6\text{ N}\) act on a particle at right angles to one another. Find the magnitude and direction of the resultant force.

When drawing the diagram for this question you can orientate it however you like so long as the two forces stated are perpendicular to one another.

This gives a right angle triangle with two known sides, and we want to find the other side and one angle.

The vector diagram shown in the Hint section is a right angle triangle with \(R\) as the hypoteneuse. Pythagoras’ Theorem gives

Using the adjacent and opposite sides allows us to determine the angle \(\theta\):

where the angle \(\theta\) is with respect to the \(5\text{ N}\) force.

Physics example: Traffic Lights - weight and tension

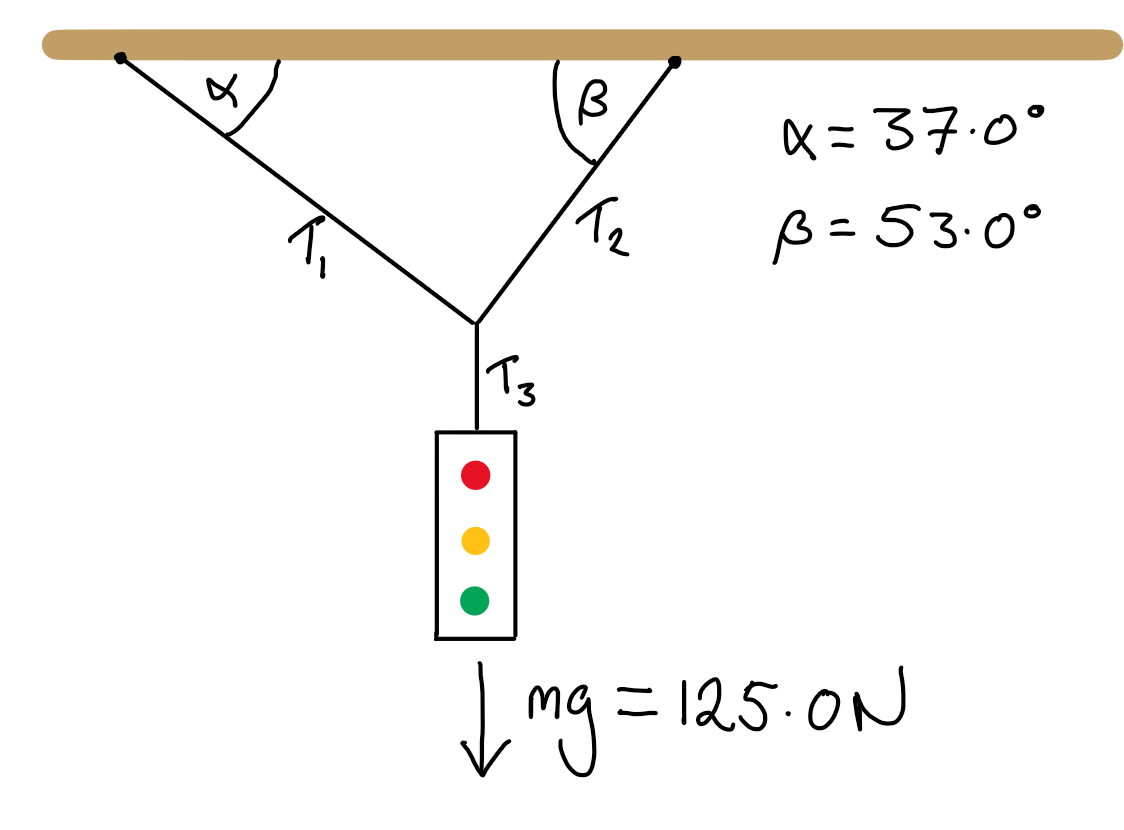

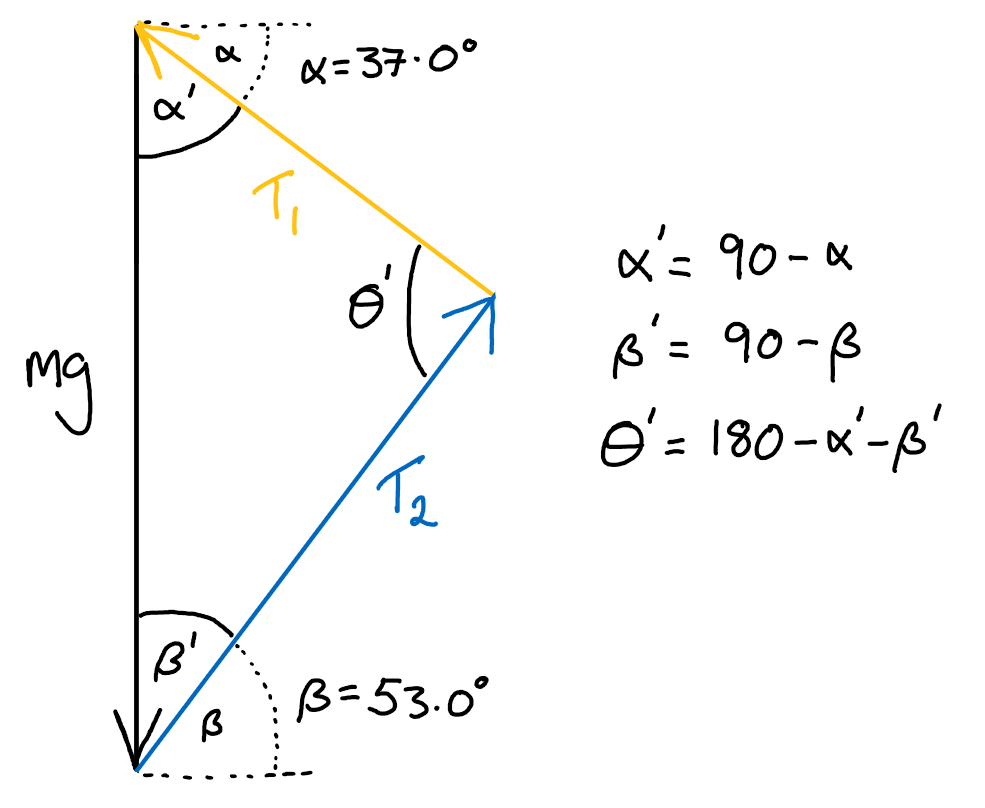

In this case we consider the type of traffic lights that are suspended from cablesold` below. We have a traffic light suspended from a single cable which in turn is suspended from two cables that make angles of \(37.0^\circ\) and \(53.0^\circ\) to the horizontal beam above. We also know that the weight of the traffic light is \(125.0\text{ N}\), and we have been tasked with calculating the tensions in each of the three cables.

Fig. 4 A hanging style set of traffic lights suspended on one vertical wire which in turn is attached to two wires that are affixed to a horizontal surface. These two wires each make a different angle to this surface and so have a different tension. The traffic light is stationary so no velocity vectors are indicated.#

Now before you jump straight in to the calculations we should take a step back and think a) about the assumptions of a system, and b) which approach we should take. The former is somewhat trivial but always worth stating: in this example I am assuming that the traffic light is stationary and therefore (from Newton’s First Law) there is zero net force in the system.

The latter point is important because taking a brief moment to pause and think about the approach gives you the time to think about which methods are valid and, of those, which are the most efficient. For the purposes of hammering this point home I’m going to solve this traffic light problem using two methods, the first being the typical approach taught in pre-University education and the second making use of the vectors that we emphasised in our earlier review of the three laws of motion.

Looking at the diagram in the question I am going to split the system up into two parts, the upper and lower, and will consider the lower part first. In this part I have two components, the weight of the traffic light \(mg\) and the tension \(T_3\). Both of these are only acting in the vertical direction which means

Next I consider the upper part and here I need to split the components of the three tensions into their horizontal and vertical components. Thus my horizontal components give

Next our vertical components give

where I have substituted the expression for \(T_1\) (equation (10)) into the second line. Now that I have an expression or value for \(T_2\) I can substitute this back in to equation (10) to find

And there we have it. We have found that \(T_1=75.2\text{ N}\), \(T_2=99.8\text{ N}\) and \(T_3=125.0\text{ N}\) to the correct number of significant figures.

The method above does work but it involved an unneccesary amount of work. By remembering that we are working with vectors we can avoid splitting our forces into their components of direction and magnitude (or in this case their horizontal and vertical), and just work with the vectors themselves.

We have assumed that the system is not accelerating which means there is no net force. Under this assumption the sum of the forces in the system should equal zero which, when expressed as a diagram, means the three vectors form a closed triangle when placed end to end. We will start by sketching this:

Fig. 5 Three arrows indicate the vector forces, one due to gravity pointing directly down, and the two force vectors point at angles with respect to the horizontal. The three vector arrows form a closed triangle because the traffic light is stationary and thus there is zero net force.#

When presented in this form I hope it is fairly clear that we have a triangle with all lengths and angles defined (even if we do not yet know all the values). Note that I’m borrowing the result from the previous method that \(T_3=mg\), but this is pretty obvious when you think about the system.

The fact that this is a triangle of vectors makes no difference; we can apply the geometry rules we all know and love to solve for the unknowns, in this case \(T_1\) and \(T_2\).

I will make use of the sine rules of triangles, which if you cannot remember it off the bat is defined as

We know all of the parameters in the left hand side so will use this part twice, first to find \(T_1\) and again to find \(T_2\). For \(T_1\) this gives

Similar steps will give you \(T_2 = 99.8\text{ N}\). These are the same as we found using Method 1, as we would expect, but the vector method is much more efficient

Resolving a contact force into normal (and frictional) components.#

Normal contact force#

Think of a particle at rest on a horizontal surface. If the surface was removed the particle would accelerate downwards due to gravity, but as it is at rest there must be some equal and opposite force acting upwards due to the surface. This force must balance the weight of the particle such that there is no resultant force and therefore no acceleration.

This force from the surface is called the normal reaction force, normal contact force, or simply the normal force and is often denoted with either \(\textbf{N}\) for normal or \(\textbf{R}\) for reaction. A key point here is that this force acts normal or perpendicular to the surface, and for instances where the surface is at an angle to the horizontal (e.g. in Worked Example 3.4 below) this normal force will not be directed vertically upwards.

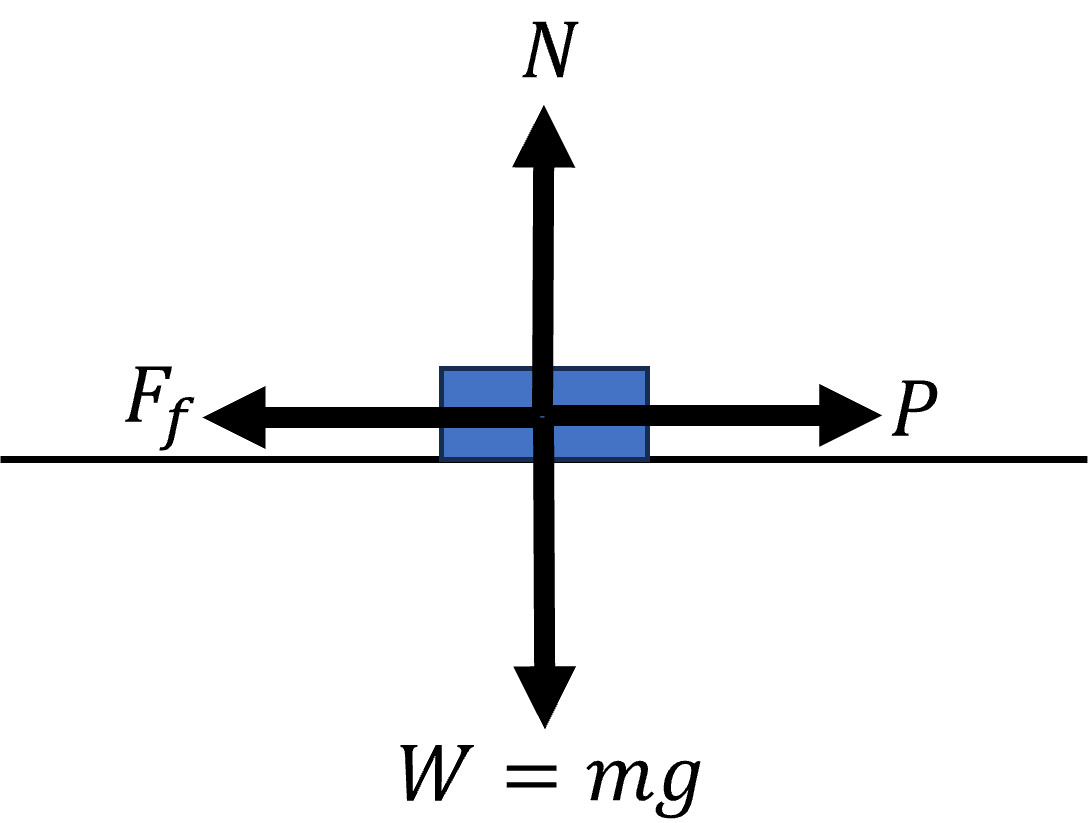

If we now try to push the particle horizontally across the surface then, up to some maximum applied force, the particle does not move. There is an additional frictional force that acts to balance the pushing force. Let us have a closer look now at this frictional force.

Friction and the coefficient of friction#

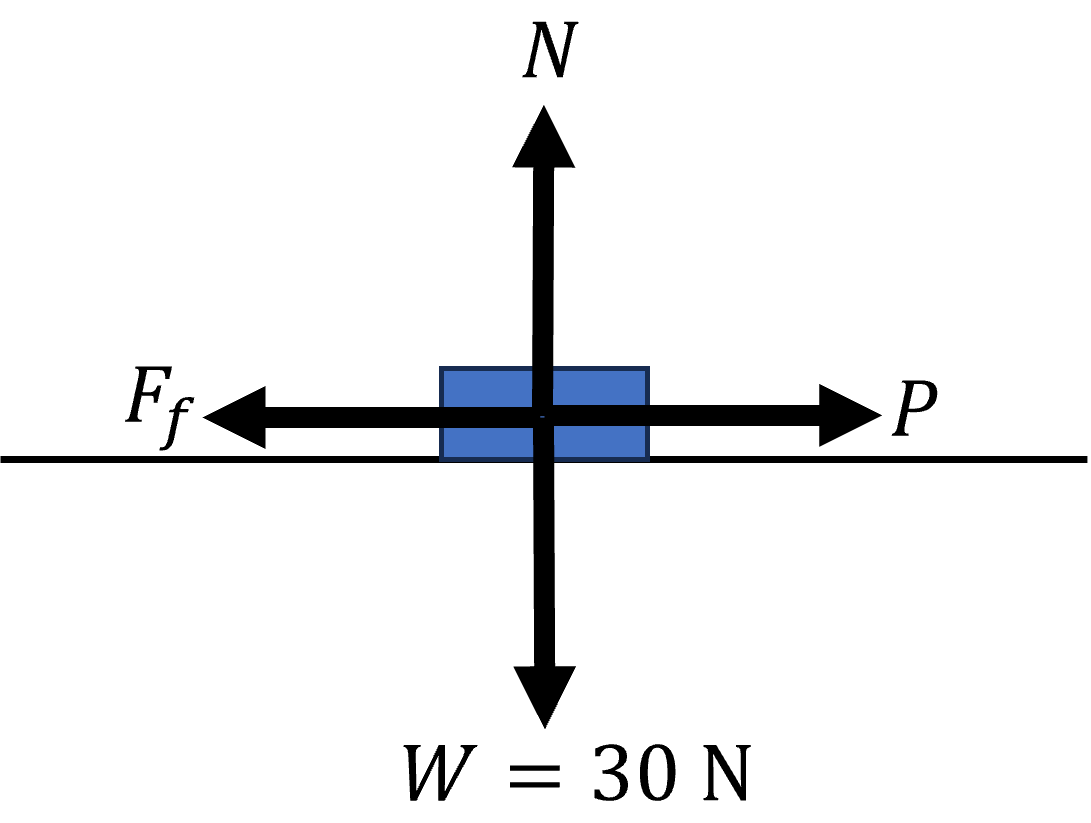

First let us visualise the system.

We have a particle of weight \(mg\) acting down, a normal force \(\textbf{N}\) acting upwards, a pushing force \(\textbf{P}\) acting to the right and a frictional force \(\textbf{F}_f\). For as long as the particle remains stationary then

What this means is that the friction force for a particular surface is not constant. It increases as the applied force \(\textbf{P}\) increases, at least up to a value \(\textbf{F}_\text{max}\) beyond which it cannot increase. At this point the particle is just about to start accelerating because the applied force is equal to the maximum resistive frictional force.

This maximum force is given by

where \(\mu\) is a constant of proportionality called the coefficient of friction

For a stationary particle, \(0\leq F_f\leq\mu R\). Once the particle beins to accelerate the frictional force opposing the relative motion remains at the constant value \(F_\text{max} = \mu R\).

Key summary points:

Friction acts to oppose relative motion.

Until it reaches its limiting value the magnitude of the frictional force is just sufficient to prevent relative motion.

When the limiting value is reached \(F_\text{max} = \mu R\).

For all rough surfaces, \(0\leq F_f\leq\mu R\).

For a smooth surface, \(F=0\).

When the particle begins to slide the frictional force has the limiting value \(\mu R\) and acts in the opposite direction of relative motion.

Worked Example 3.3 - Friction on a horizontal surface

A particle of weight \(30\text{ N}\) rests on a horizontal plane. The coefficient of friction between the particle and the place is \(\mu=0.3\). A horizontal force of magnitude \(P\text{ N}\) is applied to the particle.

Find the value of \(P\) for which the particle just begins to slide.

Worked Example 3.4 - Friction on an inclined surface

A particle of mass \(4\text{ kg}\) rests in limiting equilibrium on a rough plane inclined at \(30^\circ\) to the horizontal. Find the coefficient of friction between the particle and the plane.

Draw a force diagram, and remember to split the forces into perpendicular components. Keep in mind that, for an inclined surface, the normal force is not directly upwards.

Options are to resolve into vertical and horizontal components, or parallel and perpendicular to the plane components.

Note that \(\textbf{F}_f\) acts up the plane, since without friction the particle would accelerate down the plane.

Resolving perpendicular to the plane gives:

Resolving parallel to the plane gives:

At equilibrium \(F=\mu R\) and so:

You should retry this worked example but instead of resolving into parallel and perpendicular to the inclined surface you should find the horizontal and vertical components of all forces involved. The answer will be the same.

Vertical motion#

In the previous sections we have considered systems known as statics, meaning that while there are forces acting on the object there is no net force. The object is in equilibrium and does not accelerate, though we did start thinking about when the pushing force for example could overcome the frictional force and so the object being pushed starts to move. We will now move into the realms of dynamics and consider how applied forces cause an object to move and accelerate.

Dynamics#

In the previous sections we have considered systems known as statics, meaning that while there are forces acting on the object there is no net force. The object is in equilibrium and does not accelerate, though we did start thinking about when the pushing force for example could overcome the frictional force and so the object being pushed starts to move. We will now move into the realms of dynamics and consider how applied forces cause an object to move and accelerate.

Dynamics with constant forces#

We have already considered the case of vertical motion acting under gravity and no other forces in example 2.3. When expressing this in terms of the force of gravity and Newton’s Second Law we state:

which should come as no surprise. An object falling under gravity (without air resistance) accelerates with a magnitude equal to the acceleration due to gravity.

Other examples in which a particle can move under constant force could be through tension in a string or a constant buoyancy force.

Worked Example 3.5 - Particle lowered on a string

A ball of mass \(2.0\text{ kg}\) is attached to the lower end of a string hanging vertically. The ball is lowered with an acceleration of \(0.2\text{ m s}^{-2}\). Find the tension in the string, \(T\).

The net force is equal to the sum of the individual forces, but remember to pay attention to the relative directions of each component and the net force.

If the mass of the ball is \(2.0\text{ kg}\) then the weight is \(W=2g\text{ N}\). As the ball is accelerating downwards the net resultant force must also be acting downwards, and so:

Worked Example 3.6 - Stone through water

A stone of mass \(0.5\text{ kg}\) is released from rest on the surface of the water in a well. It takes \(2.0\) seconds to reach the bottom of the well. Assuming that the water exerts a constant buoyancy force upwards of \(2.0\text{ N}\), find the depth of the well.

Buoyancy force acts vertically upwards. You’ll also need to combine ideas in this topic (forces) with those from the previous topic (kinematic equations).

Worked Example 3.7 - Going up in an elevator

A elevator is accelerating upwards at \(a_y = 1.5\text{ m s}^{-2}\). A child of mass \(m=30.0\text{ kg}\) is standing in the elevator. Treating the child as a particle(!) find the force between the child and the floor of the elevator.

You’ll need to use Newton’s Second and Third laws here.

The child exerts a force on the floor. By Newton’s Third Law the floor exerts and equal and opposite force on the child. Let this force be \(N\), the normal force.

The resultant upward for on the child is \(R-mg\) and using Newton’s Second Law we find:

Vertical motion with drag#

In this section we are now going to go against the stereotype of a physicist and actually consider air resistance! Or more generally we are going to consider the case of a body moving through a fluid which includes both liquids and gases but can be extended to roughly approximate motion through more exotic states of matter such as polymer melts.

We are only going to think about a body in free fall as this simple geometry still presents a difficult setup to derive a form of a kinematic equation, namely the velocity of the body. You can extend the principles here to two or three dimensional motion, such as including air resistance in the projectile motion but it quickly gets very hard to solve and is not necessary for this course.

So let us jump into the problem with our usual first step of defining the system, and of course we must include our labelled schematic diagram.

Fig. 6 An object of mass \(m\) in free fall through some fluid. The velocity of the object \(v(t)\) points downwards in the direction of gravity and there is a resistive force due to the interaction between the fluid and the moving body \(R(v)\). For this course we assume that \(R(v)\) is proportional to \(v(t)\).#

You may be questioning why I have taken the time to draw out Fig. 6 as it is a rather simple one at face value. I agree but it also allows us to pin down some definitions that will help us from making mistakes down the line. I’d like to draw your attention to the fact that the force acting downwards due to gravity is constant, whereas the resistive force \(R\) is a function of velocity. For nearly every system describing motion through a fluid this will be a positive relation meaning that increasing the velocity will increase the resistive force, but it is the exact relationship between resistive force and velocity that makes this a more challenging problem.

For the purposes of this example we are going to make the assumption that the resistive force varies linearly with velocity meaning we can state that

where the constant of proportionality \(b\) depends on the shape of the body moving through the fluid as well as the interaction between the body and fluid. Thankfully we do not need to exactly define what \(b\) is so long as we make the reasonable assumption that it remains constant.

We can make use of the form of Newton’s Second Law that you have already seen (\(F=ma\)) to make a statement about the net force (and therefore net acceleration) in terms of the two component forces involved. This gives

You will see that I have used the substitution \(k=\frac{b}{m}\). It is entirely acceptable to combine multiple constants into a single constant as I have done here. Sometimes this can give some new insight into the physical meaning of the system but, more often than not, it is simply because we want to save time by only writing one letter instead of many. This efficient (read: lazy) approach is the one I have taken.

This is a differential equation which can be solved using the separation of variables method as follows

We can define this constant of integration \(c\) by considering the initial conditions of our system. As is our usual approach we can work from the assumption that the initial velocity is zero. By substituting in \(v=0\) and \(t=0\) we find \(1 = e^{-kc}\) which is only true when \(c=0\) (assuming \(k\neq 0\)). Thus

This equation shows how the velocity of a falling object in a resistive medium changes as a function of time. We can see that if \(t=0\), then \(v=0\) and when \(t=\infty\), the terminal velocity \(v_{terminal}=\frac{mg}{b}\) is obtained. Terminal velocity is reached when the gravitational force (weight) is balanced by the resistive force (eg. viscous force).

Motion of two connected particles#

Forces Involving Two Particles Connected by a Light Inextensible String#

When two moving particles are connected by a light (i.e. massless) and inextensible (i.e. constant length) string, there will be a tension in the string. By Newton’s Third Law, the forces acting on the particles due to the tension in the string will have the same magnitude but will act in opposite directions. Since the string is light and inextensible, it does not stretch, and the tension in the string is uniform throughout. This assumption allows us to consider the forces on each particle individually, while recognising that the tension will be the same for both particles, although acting in opposite directions.

When analysing the forces, we apply Newton’s Second Law to each particle. For a particle of mass \(m_1\), connected by a string to another particle of mass \(m_2\), the tension \(T\) in the string is one of the forces acting on \(m_1\), and it opposes the motion of \(m_1\) if the system is accelerating. Similarly, the tension acts in the opposite direction on \(m_2\), resisting the motion of \(m_2\) in its direction of travel.

If the two particles are moving along a horizontal surface, or suspended vertically, additional forces such as friction, gravity, or normal contact forces may need to be considered. For horizontal motion on a smooth surface, we ignore friction, but on a rough surface, we introduce frictional forces, which oppose the direction of motion. For vertical motion (e.g. one particle suspended vertically while the other moves horizontally), gravity becomes a significant factor. The motion of the system is then affected by the gravitational force acting on each particle, with the tension in the string balancing part of this force.

In either case, the particles share a common acceleration, since the string is inextensible. This common acceleration, \(a\), can be found by analysing the forces acting on each particle and solving the system of equations that result from Newton’s Second Law.

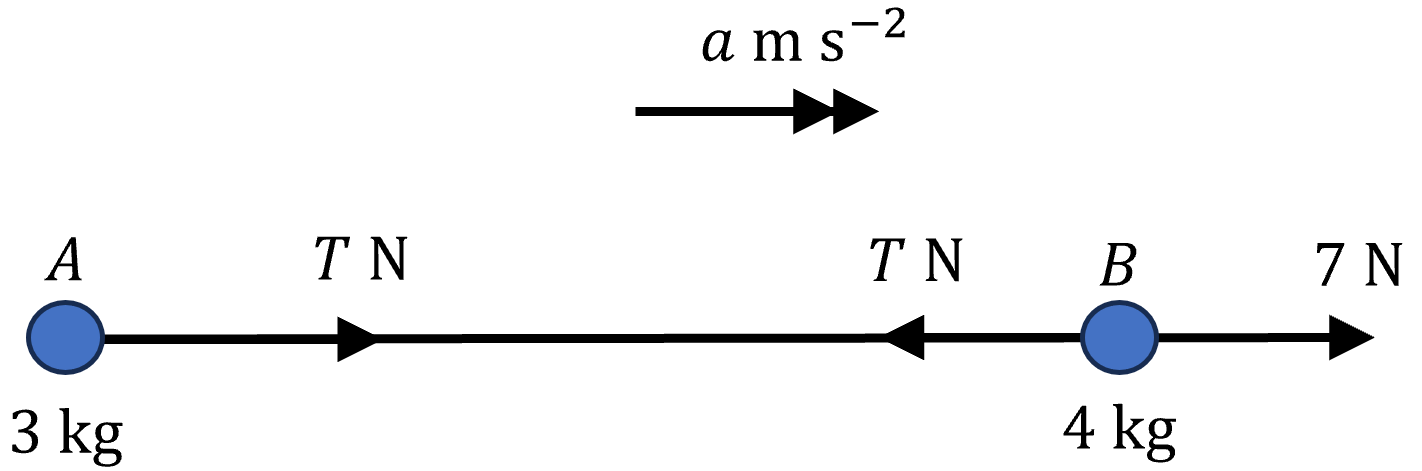

Worked Example 3.8 - Two connected particles

Two particles \(A\) and \(B\) of masses \(m_A=3.0\text{ kg}\) and \(m_B=4.0\text{ kg}\) connected by a light inextensible string are at rest on a smooth horizontal surface. A force of magnitude \(7.0\text{ N}\) is applied to particle \(B\) in the direction \(AB\) (i.e. away from particle \(A\)). Find:

the acceleration of particles \(A\) and \(B\)

the tension in the string \(T\).

The diagram helps here, either in terms of ensuring the signs of forces are correct or by constructing a force diagram and solving using arrows (both are equivalent, just different ways of viewing the problem).

Part 1

The motion of the particles \(A\) and \(B\) need to be considered separately, but a key observation is that they will both be accelerating by the same amount \(a\) (because they are connected by the string, and \(B\) is pulling \(A\)).

Letting the tension in the string be \(T\) we use Newton’s Second Law twice, once for each particle.

For particle \(B\)

For particle \(A\)

Combining these two equations gives

Part 2

Substitute this value for \(a\) into either of the equations for the particles (I’ll use the one for \(A\) because it’s less complicated):

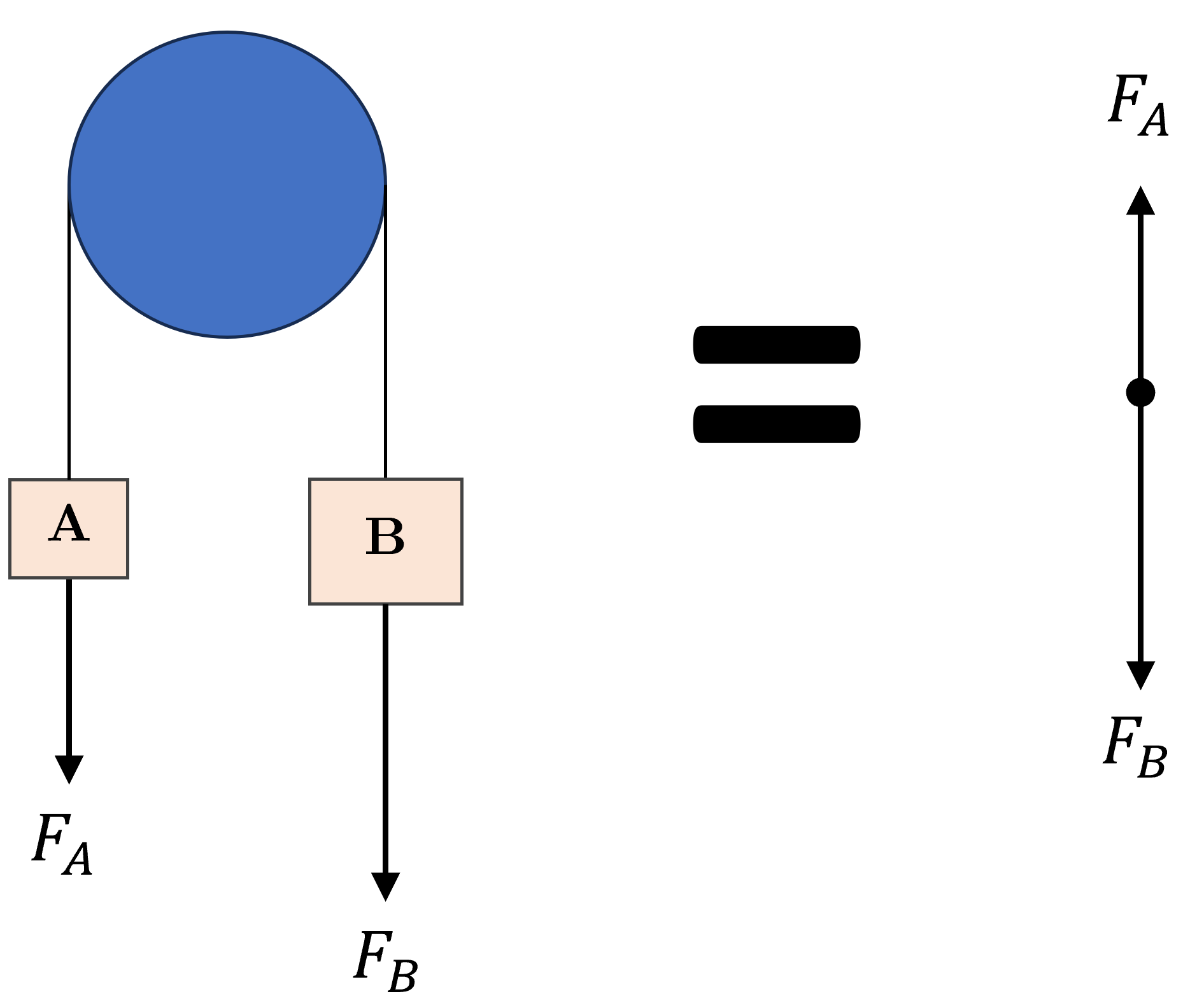

Problems involving pulleys.#

For all of the situations we will consider in this course the pulleys are frictionless and the strings involved are light (no mass) and inextensible (fixed length).

The introduction of a pulley can make the system seem more complicated, though the key thing to keep in mind is that a pulley simply changes the direction of the forces. Some people like to think of them as a theoretical pivot point on a force diagram, so if you had a system in which two masses are connected over a pulley and hanging vertically, the system is (from the perspective of forces) the same as a system in which you rotate one of the force arrows. This is shown below.

The challenging part of pulley systems is thinking about relative motion and action. For example in the previously mentioned scenario both masses are being acted on by gravity, and these forces \(F_A\) and \(F_B\) are both acting vertically downwards. However the force on \(A\) would act to accelerate \(A\) downwards and \(B\) upwards via tension in the string, and the force on \(B\) would do the opposite.

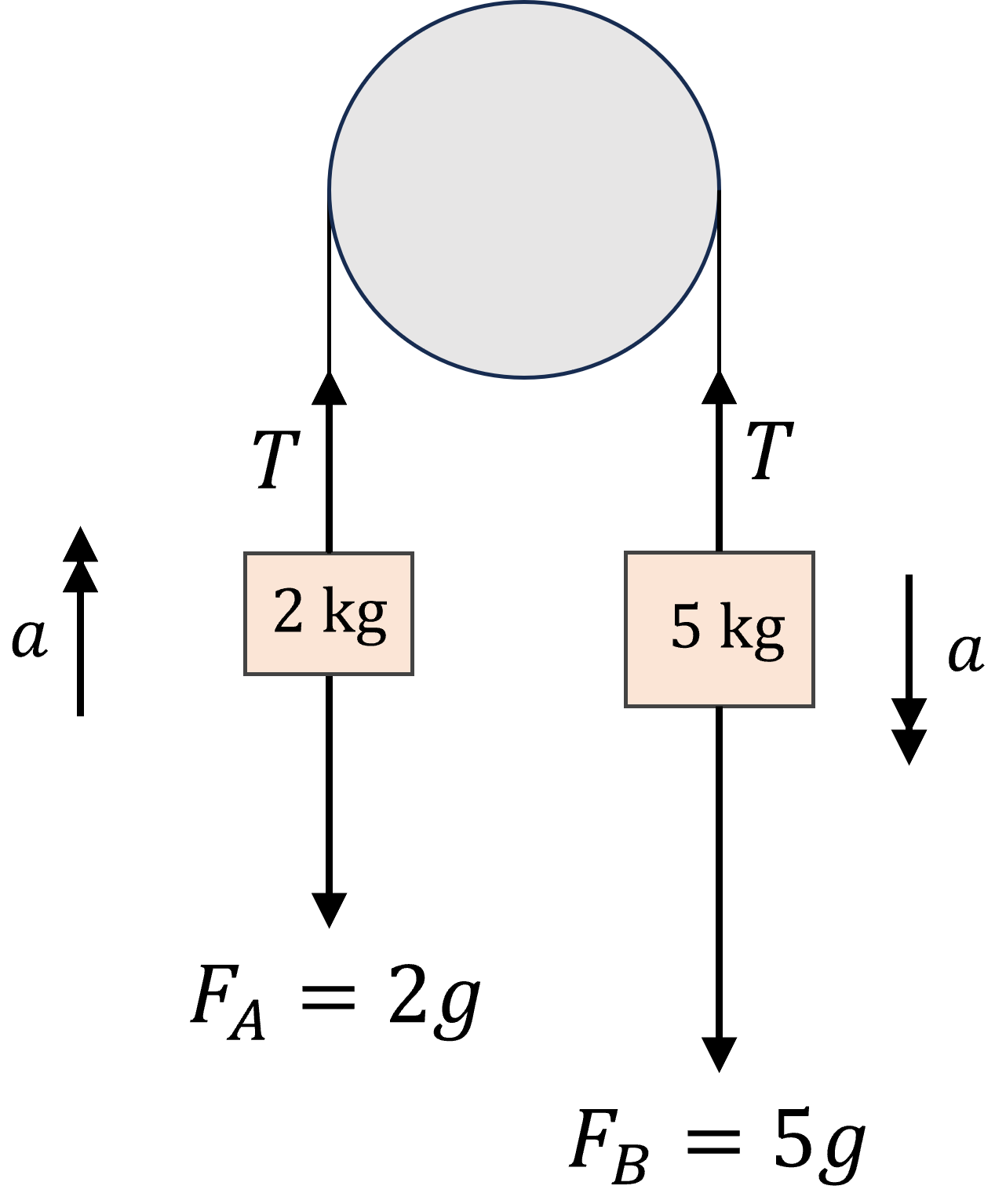

Worked Example 3.9 - Two particles connected over a pulley with vertical motion only

Partcles of masses \(5.0\text{ kg}\) and \(2.0\text{ kg}\) are attached to the ends of a light inextensible string which passes over a smooth fixed pulley. The system is released from rest.

Find the acceleration of the system and the distance moved by the heavier mass in the first \(3.0\) seconds of motion. Assume that neither mass reaches the pulley.

Redraw the diagram above with all forces labelled (gravity and tension), and resolve for each mass to then find the net force on the whole system.

Since the masses are released from rest the heavier object will accelerate downwards with acceleration \(a\), pulling the lighter object upwards with the same acceleration.

Let the tension in the string by \(T\) and has the same value throughout the string as the pulley is smooth.

For the \(5\text{ kg}\) mass:

For the \(2\text{ kg}\) mass:

Adding these two equations gives

To find the distance moved by thr \(5\text{ kg}\) mass in 3.0 seconds we use the kinematic equations with the value for the acceleration we have just found.

The known quantities are:

v_0 = 0

a = \frac{3g}{7}

t = 3.0 Using \(s = v_0t + \frac{1}{2}at^2\) we find:

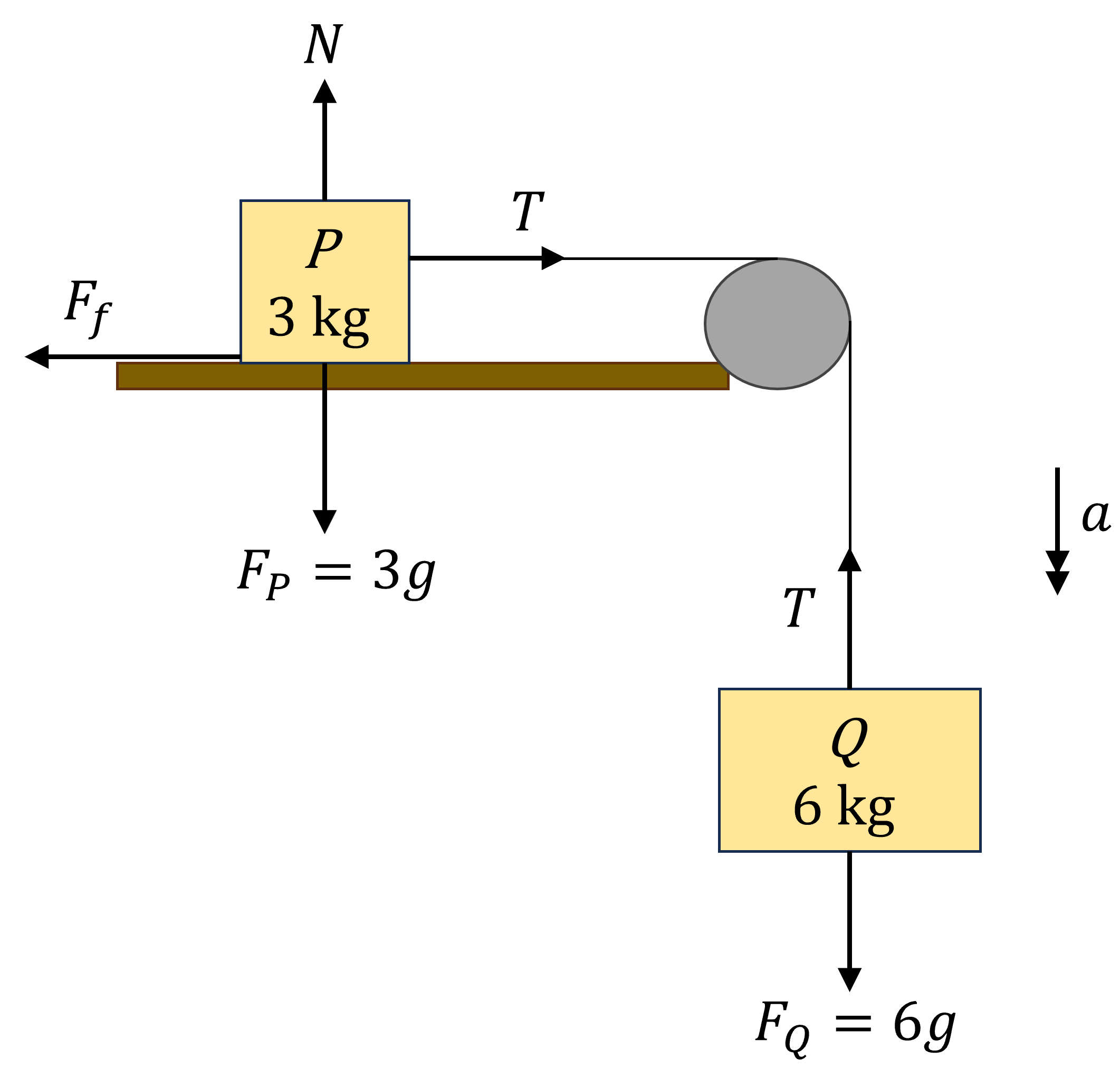

Worked Example 3.10 - Two particles connected over a pulley in 2 dimensions

Two particles \(P\) and \(Q\) of masses \(m_P=6.0\text{ kg}\) and \(m_Q=3.0\text{ kg}\) are connected by a light inextensible string. Particle \(P\) rests on a rough horizontal table. The string passes over a smooth pulley fixed at the end of the table and particle \(Q\) hangs vertically. The coefficient of friction between \(P\) and the table is \(\mu=\frac{1}{3}\).

The system is then released from rest. Find (in terms of \(g\)):

the acceleration of \(Q\),

the tension in the string \(T\), and

the force exerted on the pulley.

This may seem tricky because we have horizontal and vertical motion, but remember that the system should be considered in terms of the direction of forces relative to the motion.

You may find it helpful to draw a schematic with forces labelled, and then redraw it to a one dimensional version by ‘rotating about’ the pulley.

The tension in each part of the string is the same since the pulley is smooth, which we shall label as \(T\).

Part 1

Particle \(P\) does not move vertically, so the net vertical component of force must be zero meaning

As \(P\) is moving along the table the friction is the limiting (kinetic) friction meaning \(F_f = \mu N = \frac{1}{3}\times 6g = 2g\). Using Newton’s Second Law for the horizontal force components on \(P\) we find:

Resolving vertically for \(Q\) gives

Part 2

Substituting this value for \(a\) into the equation above for the horizontal forces acting on particle \(P\) gives:

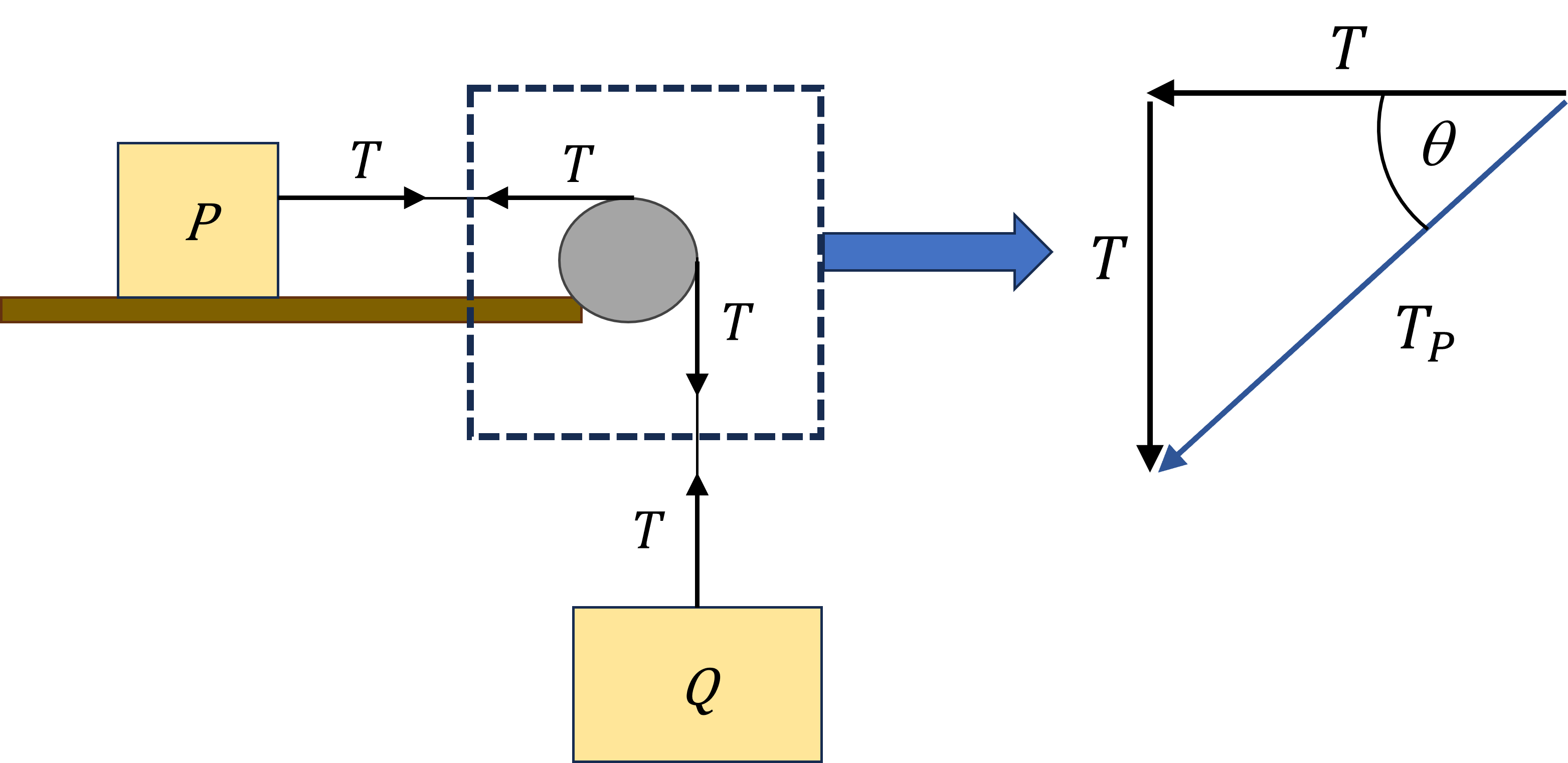

Part 3

To find the force exerted on the pulley consider the horizontal and vertical parts of the string separately as shown below.

The tension in each part of the string is the same. By Newton’s Third Law there will be equal but opposite tensions at the pulley ends of the strings, also equal to \(T=\frac{8g}{3}\) as found in part 2.

To calculate the resultant force on the pulley, \(T_P\) we apply the triangle law of addition of vectors which gives:

and the direction is

where this angle is downwards from the table, as indicated in the diagram. If you were using the typical definition of angles being defined anticlockwise from the positivie \(x\) direction (to the right) then \(\theta = 225^\circ\).

Gravity - Not assessed!#

Disclaimer: This topic is more for completeness and is not part of the assessed course itself.

When we entertain ourselves by studying how a mass behaves in free fall we typically make two assumptions, that there is no air resistance and that gravity is the only force acting on the mass. This second assumption relies on the approximation that for “small distances” the gravitational force is constant or, more correctly, the change in the force over the small distance is negligible. But what happens if we wanted to calculate the time taken to impact on the Earth, or the impact velocity of a tool dropped by an astronaut undergoing a space walk on the ISS? The force due to gravity is described by

where \(G\) is the gravitational constant, \(m\) and \(M\) are the masses of the two interacting bodies, and \(r\) is the distance between the two. You may have already seen this but if you have not then worry not as we will cover it in Lecture 11. For now, just accept it as true.

We are going to now calculate the velocity the dropped tool will have when it hits the surface of the Earth, assuming no atmospheric effects and the tool is dropped from rest.

If we know the force due to gravity then we can state the acceleration due to gravity,

and we’ll define \(R_E\) as the radius of the Earth, \(h\) as the height of the ISS above the surface of the Earth, and \(r\) is the radial distance of the tool from the surface of the Earth (so \(r=0\) occurs then the tool hits the ground).

The challenging part to this problem comes when we try to link the above equation for acceleration due to gravity with the differential form of acceleration, \(\frac{\mathrm{d}v}{\mathrm{d}t}\). The acceleration due to gravity acting on the tool is not constant in time as for later times the acceleration will be larger (i.e. the tool is closer to the Earth). One approach to solving this could be to try and calculate the time taken to hit the ground and then find the velocity, but this is a bit tricky as you need an expression for how the acceleration varies in time.

Instead we can change the differential!

So now we can solve by using the expression for \(a_g\) above, rearranging and integrating,

A sense check here would be to see what happens when \(h\ll R_E\) meaning the tool is close to the surface and so the gravitational field is roughly constant. When this limit is taken you get the same result you would from the standard suvat-type kinematic equation,

This may be a rather contrived example but it has some wider reaching benefits beyond the immediate topic. The important part is that if you have a mathematical description for the force related to some physical interaction then you can use this to create lots of insightful models. For example if you knew how the force between two charged particles behaved as a function of separation between them, then you could work out the velocity of one particle if released from rest and the second particle was fixed. Or you could model the motion of charged particles through a field, which forms the basis of an experimental technique known as mass spectrometry.