Lecture 10 - Torque and rotational acceleration#

We are almost at the end of our study of rotational kinematics, but there are still two topics that we have only covered in the linear kinematics section. These as the rotational equivalent of force known as torque and rotational equivalent of momentum known, unsurprisingly, as angular momentum.

Torque#

Definition of torque#

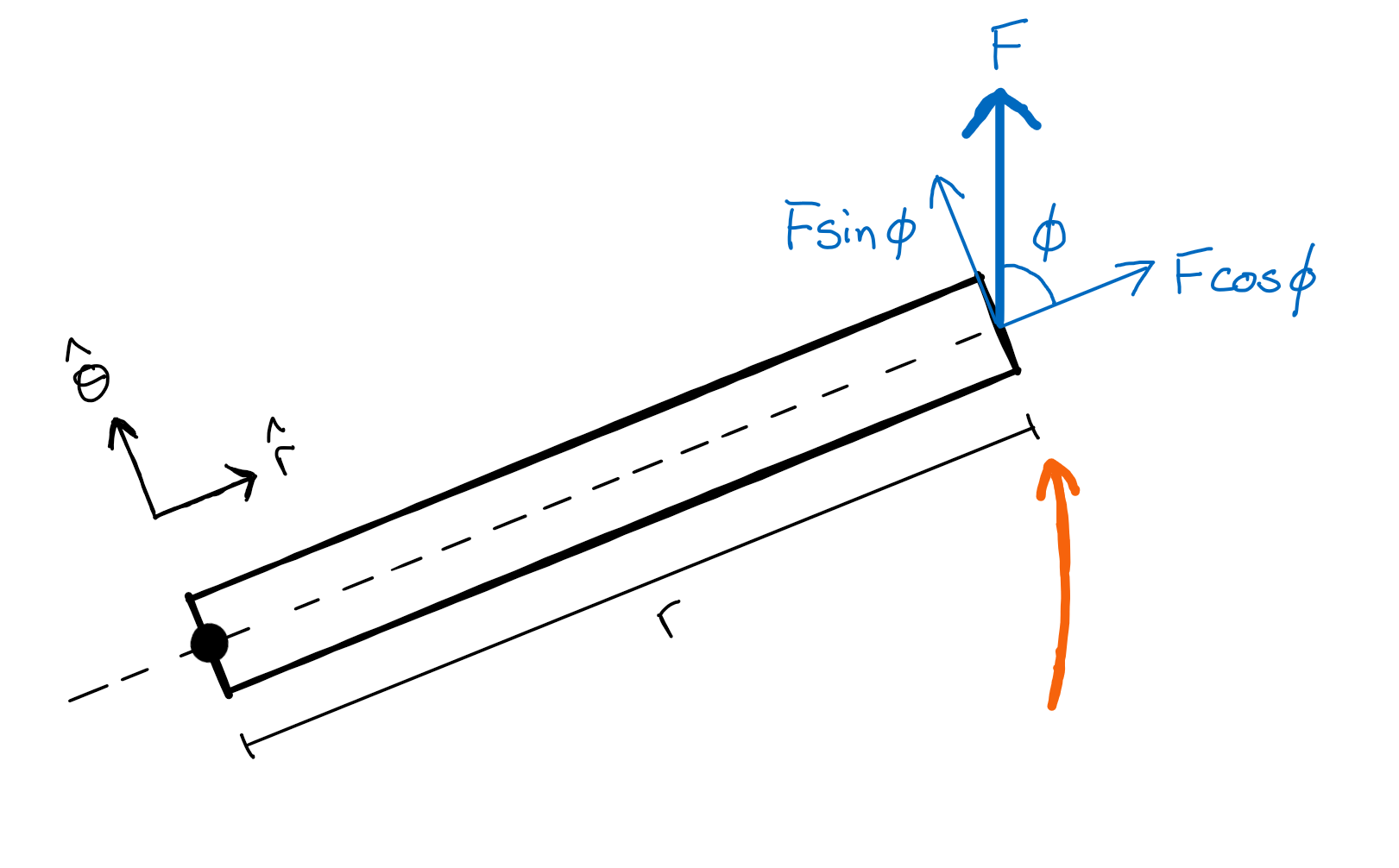

When we considered Newton’s Second Law we stated that a non-zero net force will result in some acceleration (assuming the mass remains constant). Although this is true it is not the whole picture. It is entirely feasbile that a body experiencing some external force may not accelerate in a linear motion but instead begins to rotate. In this case we are concerning ourselves with the force acting in a direction perpendicular to the line connecting the pivot point and the point (or points) on the object where the force(s) are being applied. Let us consider a diagram of a bar of length \(r\) with a fixed pivot point at one end and a force applied to the other end (Fig. 28).

Fig. 28 A force \(F\) is applied to the end of a bar of length \(r\) which is fixed to a pivot point at the opposite end. This force causes the bar to rotate.#

We assume, for the sake of generality, that the force \(F\) is acting in some direction between \(\hat{\textbf{r}}\) (i.e. pulling on the bar) and \(\hat{\boldsymbol{\theta}}\) (i.e. only acting to induce rotation). It is the component of the force acting perpendicular to the length of that bar that will result in some angular acceleration of the bar, and this component is \(F_\text{rot} = F\sin\phi\). Therefore the leverage or torque \(\boldsymbol{\tau}\) on the bar is

If we have multiple forces acting on the body then the total torque is equal to the sum of the individual torques, i.e.

Angular acceleration and torque#

Any net force will result in an acceleration, as we know from Newton’s Second Law. What we are currently missing is a direct relationship between the torque and resulting angular acceleration, in the same way that we know the relationship between force and acceleration along a straight line.

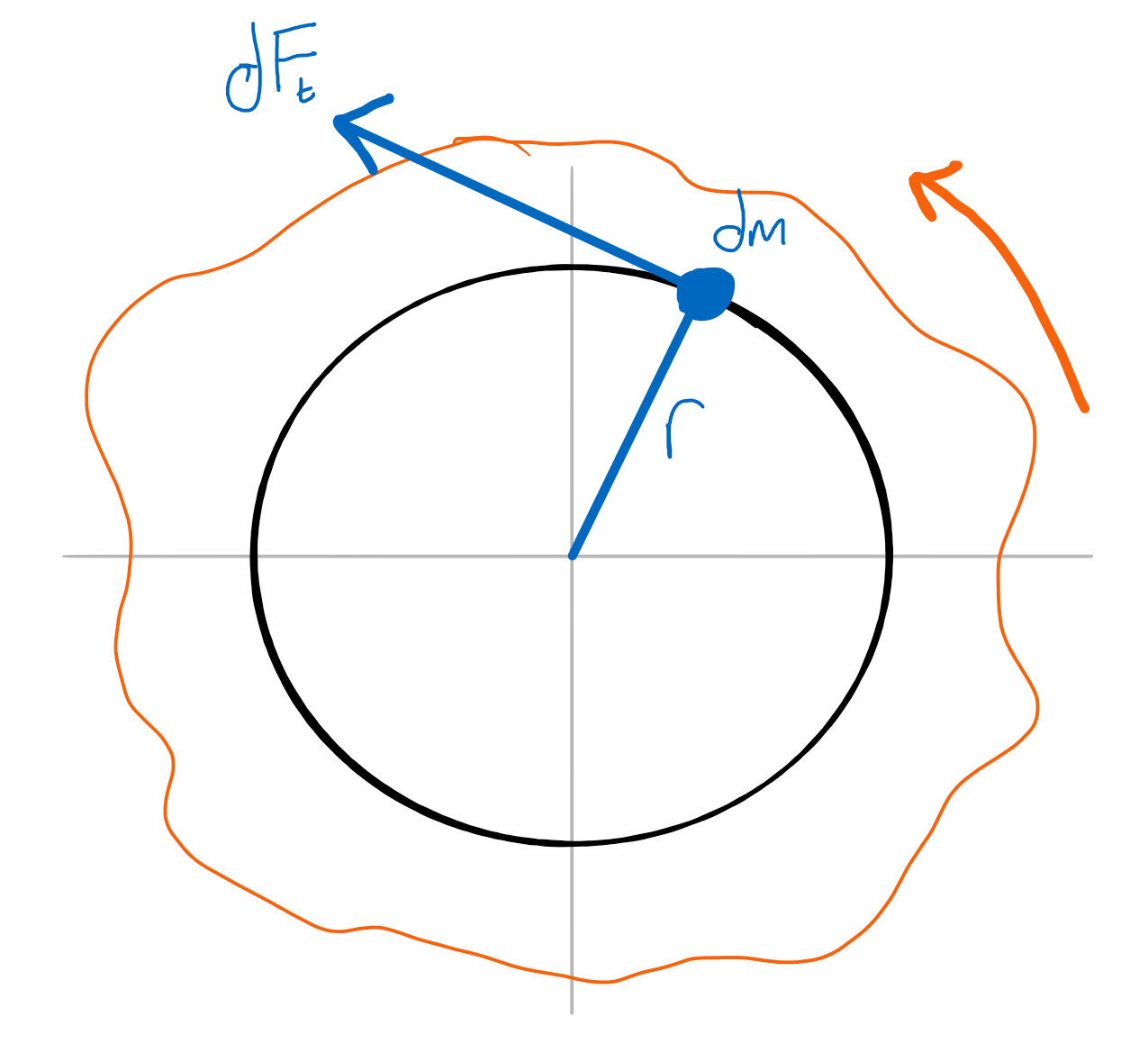

We can consider a solid body of mass \(m\) rotating about some axis as the sum of many many small mass elements \(\mathrm{d}m\). We have already used this idea when deriving the total energy of a rotating body (specifically Fig. 22), but now we are applying some small force to each of these masses such that a tangential force \(\mathrm{d}F_t\) is applied as shown in Fig. 29.

Fig. 29 A force is applied to a random shaped mass that causes it to rotate about an axis perpendicular to the plane of the diagram. The mass is split into small mass elements each of which has a tangential force \(\mathrm{d}F_t\) acting on it.#

We use Newton’s Second law to state

where \(a_t\) is the tangential acceleration. We also know that the torque acting on this element is

Equation (56) defines the relationship between the tangential and angular accelerations, and thus

To find the net torque we integrate over the entire mass and make use of the fact that the angular acceleration is the same for all mass elements if the body is rigid. Therefore

A return to the pendulum#

Do you remember way back in Lecture 2: the pendulum where we derived the differential equation (equation (18)) for a pendulum using the components on the gravitational force acting along the path of the pendulum? A pendulum is a rotating system though, albeit one that never completes a full rotation1, but we can still use our rotational dynamics and our new understanding of torque to find the same result.

Starting from our definitions of torque

We can define the torque acting on the pendulum in terms of the length and force due to gravity vectors as

Next the angular momentum can be written as

If \(\boldsymbol{\tau} = \dfrac{\mathrm{d}\textbf{L}}{\mathrm{d}t}\) then \(|\boldsymbol{\tau}| = \dfrac{\mathrm{d}|\textbf{L}|}{\mathrm{d}t}\) which gives

which is exactly the same as equation (18) we derived earlier.

Angular momentum#

Definition of angular momentum#

To find the total angular momentum of a solid rotating body we once again consider it to be made of small mass elements \(\mathrm{d}m\) each some distance \(r_i\) and moving with some momentum \(p_i\). The angular momentum for each element \(L_i\) is

So the total angular momentum of the body rotating about the \(z\)axis is simply the sum of the angular momenta for the individual mass elements, i.e.

Often we are more concerned with how the momentum is changing, so by taking the time derivative of equation (59) we find

This final equation should come as no surprise. Back in Lecture 3 we saw the more general form of Newton’s Second Law (equation (21)) which states that the rate of change of linear momentum is equal to the net force applied. Here we have found a rotational equivalent between the rate of change of angular momentum and the net applied torque.

Conservation of angular moment#

If the net external torque acting on a rotating system is zero then the total angular momentum is constant. This is very similar to the conservation of linear momentum case but extra care must be taken when working with angular momentum as we must consider the distribution of the mass (due to the moment of inertia term in equation (59)).

There are some really good physical examples of this, one of which I hope you are all familiar with but if not you can find some good videos on YouTube. The system I am thinking of is an ice-skater who is performing a spin on the spot. When they are spinning with their arms outstretched they are rotating with some angular velocity but if they bring their arms in suddenly their rotational velocity increase. We assume they have not suddenly changed their mass and we can see there are no external forces acting on them. The cause of this increased angular velocity is their change in mass distribution.

Consider the simplified equation for conservation of angular momentum for this system.

If the ice skater decreases their moment of inertia \(I_\text{after}\) then their angular velocity \(\omega_\text{after}\) must increase by an equal factor so that the conservation of angular momentum equation above is balanced.

Lecture Questions#

Question 1

Suppose that while opening a 1.0 m wide door you push against the edge farthest from the hinge, applying a force with constant magnitude \(0.90\) N at right angles to the surface of the door. How much work do you do on the door during an angular displacement of \(\Delta\phi=30^{\circ}\)?

A door is equivalent to a uniform rod, at least in terms of the moment of inertia. Just be careful to ensure you’ve got the right axis of rotation location.

For a constant torque the work done is \(W=\tau \Delta\phi\) and the torque is

where \(\theta\) is the angle between the applied force and the length vectors. Therefore

Question 2

A uniform meterstick is initially standing vertically on the floor. If the meterstick falls over, with what angular velocity will it hit the floor?

Assume that the end in contact with the floor does not slip.

This system can be modelled as a thin solid bar or rod, but pay attention to where the axis of rotation is. You’ll need to use a conservation law so it may help to write out what information you know that can be used in one of these laws.

The mass of the meterstick is \(M\) and total length is \(l\) such that the centre of mass is initially a height \(y_i=\frac{l}{2}\) above the floor. The motion of the meterstick is of a rod rotating about a fixed axis through the point of contact with the floor and therefore has a moment of inertia \(I=\dfrac{ML^2}{3}\) (this is a result of a ``standard’’ shape configuration, covered in these notes / textbook).

Assuming conservation of energy throughout the fall the sum of the potential and rotational energies before falling equals the sum of the energies just before hitting the floor, i.e.

where we make use of the initial condition \(\omega_i=0\) (stationary at the start) and \(y_f = 0\) (meterstick is laying on the floor at the collision, so has zero height from floor). Therefore

Question 3

The rotor of the gyroscope on the Gravity Probe B experiment is a quartz sphere of diameter \(3.8\text{ cm}\) and mass \(7.61\times10^{-2}\text{ kg}\). To start the sphere spinning, a stream of helium gas flowing into an equatorial channel in the surface of the housing is blown tangentially against the rotor.

What torque must this stream of gas exert on the rotor to accelerate it uniformly from \(0\) to \(10000\) rpm in 30 minutes?

What force must it exert on the equator of the sphere?

If you struggle with torque and angular acceleration then consider a linear analogue with force and acceleration.

For part 2 you should draw out the system and include the force vectors, from which you can identify any angles between vectors and hopefully simplify the system.

1 The final angular velocity \(\omega_f=1.05\times10^3 \text{ radians s}^{-1}\) and so the angular acceleration is

The required torque is therefore

2 The gas is blown tangentially against the rotor, such that the angle between the force from the gas and the radius vector of the sphere is \(90^{\circ}\).

Question 4

Suppose that a pottery wheel is spinning (with the motor disengage) at 80 rpm when a \(6.0\text{ kg}\) sphere of clay (radius \(R=8.0\text{ cm}\)) is suddenly dropped down on the center of the wheel.

What is the angular velocity after the drop, if the moment of inertia of the pottery wheel itself if \(I_{\text{wheel}}=7.5\times10^{-2}\text{ kg m}^{-2}\)?

The system should have some conservered property that you can use. But it’s important to justify that this conservation is valid.

As there is no external torque on the system, the angular momentum of the system is conserved

The clay sphere has a moment of inertia \(I_{\text{clay}}=\dfrac{2}{5}MR^2 = 1.5\times10^{-2}\) and so the final angular velocity is \(I_f = 7.0\text{ radians s}^{-1}\).

- 1

Unless you really push the pendulum. But then we are definitely away from the small angle domain…