1.1 What is soft matter?#

Overview#

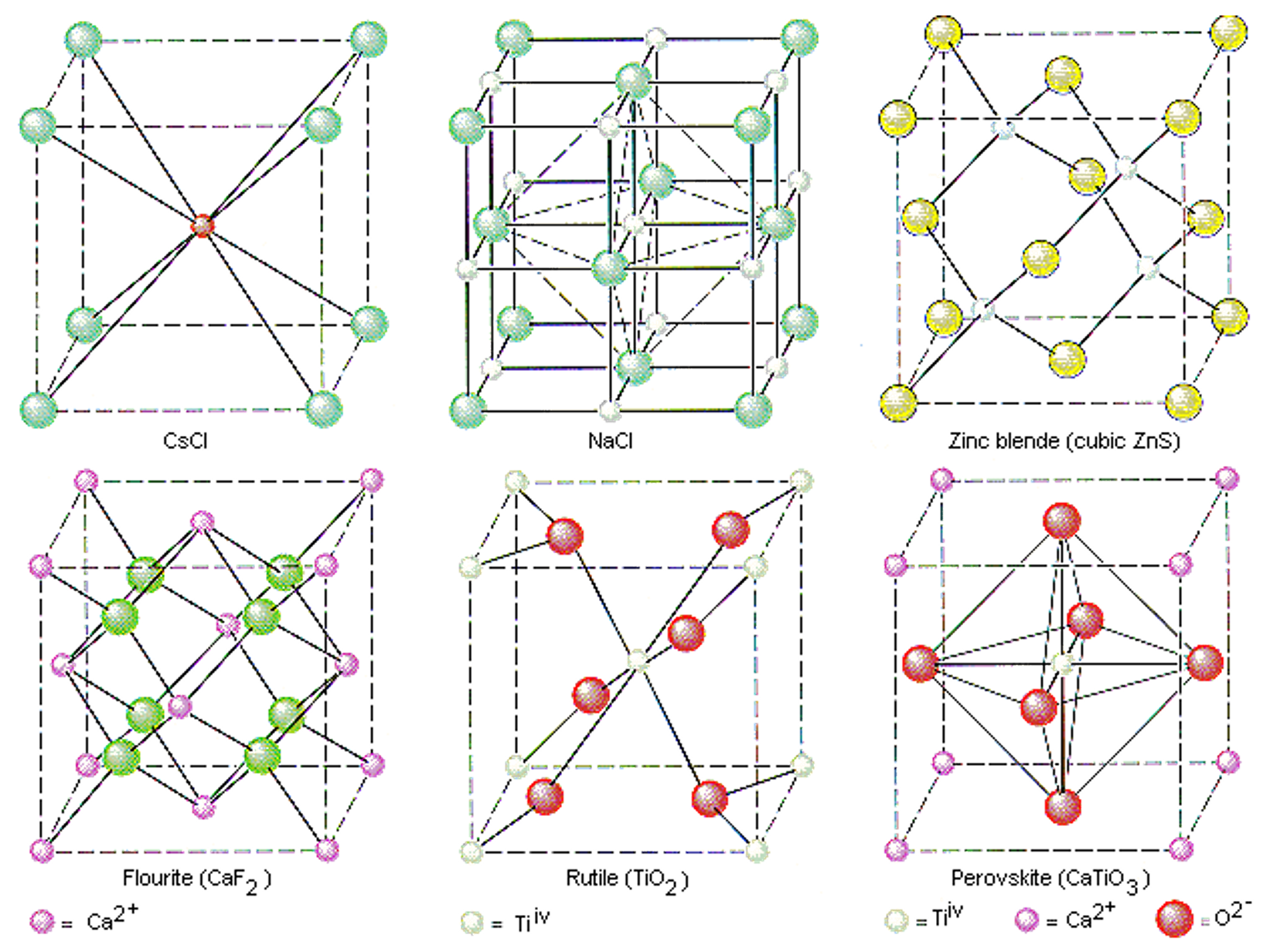

Before we jump straight into the topic of what soft condensed matter is, it can be more useful to think about what it isn’t. The existence of soft condensed matter suggests the existence of hard condensed matter, and this is something you are already more than familiar with. Often we would shorthand these as solids; yes, those solids that you’ve been learning about since secondary / high school. Rigid materials at the macroscopic level, and at the atomic level we observe a high degree of order amongst the atoms (see Fig. 1). These well defined structures also persist over long ranges, defined with respect to the typical bond length or size of a unit cell.

Fig. 1 Common crystal structures including BCC (top left, CsCl) and simple cubic (top middle, NaCl) as well as some more complex but more useful materials. For example perovskites (bottom right) are a leading contender for high efficiency photovoltaic materials.#

We are all also familiar with what a liquid is, particularly in comparison to a solid. When we heat a solid above its melting point the well defined and long range structure breaks down as the bonds between atoms are broken. We then have a material in which the individual atoms are able to move and are more randomly distributed across larger lengthscales. At the macroscopic level we now have a material that will flow under an applied force (more on this in the section on Shearing).

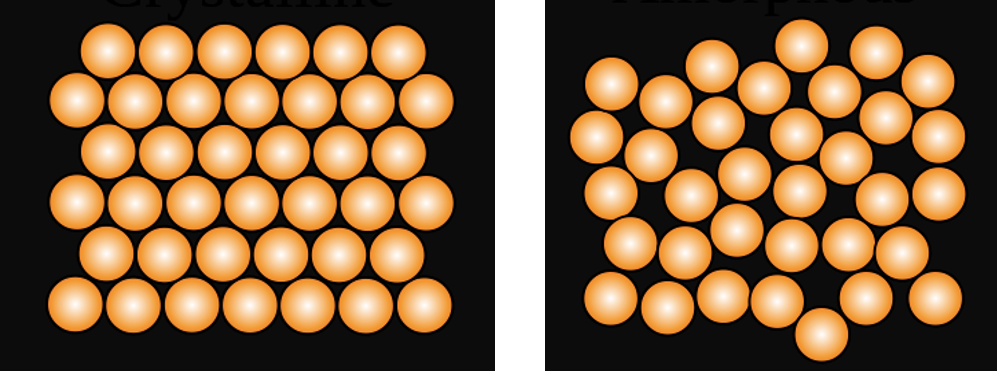

I have no doubt that you are all already familiar with what a solid and liquid look like at the atomic level but I do appreciate a nice diagram, so see Fig. 2 for your viewing pleasure. Although it may seem a waste of time for me to remind you about this, it does help us to visualise what soft condensed matter might look like by comparison.

Fig. 2 Representation of a solid (left) and liquid (right) at the atomic level. Note that the atoms in the solid are in a regular pattern and that this pattern persists across the whole figure. The atoms in the liquid are more randomly scattered and there is no long range order or pattern to their placement.#

If we are taking the comparison perspective then you might expect that if hard-condensed matter is made up of highly ordered and well defined structures then soft condensed matter surely is highly disordered and lacks and well defined structures. This is broadly true for some types of soft matter (glasses, for example) whereas other soft materials such as semi-crystaline, self assembled and biological systems can exhibit a surprising amount of structure and order. The difference between ordered hard and soft materials is that, generally, the former will more readily form the well defined structures whereas the latter often require specific internal (i.e. molecular structure) and external (e.g. temperature, applied field, etc) factors to promote the ordered structure.

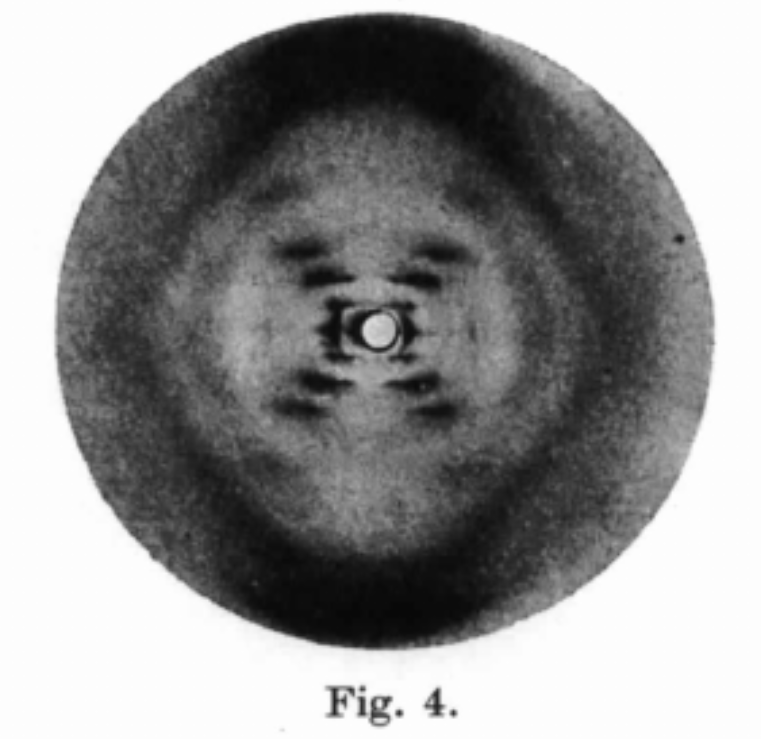

A great example of this is the work of Rosalind Franklin and her graduate student Raymond Gosling in identifying the structure of DNA. They were already aware that mechanical treatment and drying could obtain highly ordered specimens of sodium thymonucleate (NaDNA), and they investigated the influence of humidity and sample preparation that led to them being able to obtain high quality x-ray scattering images of DNA. Fig. 3 is the infamous Photo 51 that other scientists “borrowed” without consent, published their own work using this, and subsequently got all the recognition.

Fig. 3 Photo 51 from the work by Franklin and Gosling published in 1953. Their process allowed them to produce highly ordered NaDNA samples that would scatter x-rays into a diffraction pattern (central black X in figure). This scattering profile could only occur if the DNA was a double helix, rather than other structures that had been proposed by theorists of the time.#

Sidenote:

Although this is not a textbook definition, one way that I differentiate between hard- and soft- matter relates to the individual units. Hard condensed solids are generally atomic systems, meaning that the individual units are an atom, or sometimes small molecules, and these units are found in an ordered structure when in the solid state. The units of a soft matter system are large molecules or supra-molecular units.

Or as we will see when it comes to modelling molecules in systems and in motion, it is sometimes helpful to take the even more crude differentations of small spheres (atoms - hard matter) versus long strings (large molecules - soft matter).

Bonds in hard- and soft-condensed matter.#

The type and amount of order and structure does give some indication as to whether a material is classed as hard- or soft-condensed, as does the nature of the individual units that make up the solid. Another related element to consider is the type of bonds that these different types of units can make with each other when forming the solid phase.

The atoms in a hard-matter crystal will form stronger interatomic bonds via covalent, ionic / electrostatic or metallic bonds. These should all be familiar to you from second year so I will not go into more detail here. The molecules in soft condensed matter tend to form weaker, typically temporary or transient bonds between molecules. Key processes to be aware of are in Table 1.

Types of interatomic bonds

Type |

Summary |

|---|---|

Van der Waals interactions |

An asymmetry in the electron density of an atom or molecule creates a temporary dipole. This dipole can then interact with nearby atoms or molecules that are either already charged or it can induce an opposing dipole in a neighbouring molecule. |

Hydrogen bonding |

When a hydrogen atom is covalently bound to a more electronegative atom, the asymmetry in the electron density of the hydrogen means that another electronegative atom can weakly bind with the more ‘positive side’ of the hydrogen. An example of hydrogen bonding is between base pairs of DNA (see Fig. 4). |

screened electrostatic interactions |

These types of interactions involve the molecules of interest (free or bound to a surface) and other ions that are typically dissolved in a solvent. These free ions are able to move and act as a screen in the electric field between two charged molecules that are otherwise attracted or repelled as per Coulombic forces. |

hydrophobic interaction |

Although the molecules in liquid water are not in a crystalline ordered state, they still form a hydrogen-bonded network due to the asymmetry of the water molecule structure. When a molecule that cannot form hydrogen bonds is introduced to this network it perturbs the local structure which leads to a decrease in entropy and thus increases the free energy (more on this later). If more than one molecule is added to the water then each of them will cause a local perturbation, but this perturbation is decreased if the non-water molecules cluster; if you had a cluster of molecules then only the outer shell is interracting with the water network, and the total excluded volume is smaller than the sum of excluded volumes of individual molecules (again, more on this later). This tendancy for non-water water molecules to attract is the hydrophobic interaction and is of order \(5-10\text{ meV}\) |

Fig. 4 Hydrogen bonding between base pairs of DNA. The hydrogen associated with an NH bond is weakly ‘shared’ (dashed line) with either an oxygen or nitrogen atom (both are more electronegative than the hydrogen atom) in the opposing base pair unit. The stronger NH bond means that the single electron associated with the hydrogen atom is more likely to be ‘found’ near the N atom, which in turn creates a small hydrogen dipole that can interact with other atoms.#

You’ll notice that I talked about the two different bonding groups in terms of them being strong or weak1. These are strong or weak in comparison to thermal energy. A carbon-carbon covalent bond has an average energy of \(5.72\times10^{-19}\text{ J} (\approx 3.6\text{ eV})\) whereas thermal energy at room temperature is of order \(3\times10^{-21}\text{J} (\approx 0.02\text{ eV})\). In other words, the bonds associated with hard condensed matter are (very roughly) \(100\) times larger than thermal energy, which is the reason why hard-condensed matter remains solid at room temperature even taking into account the statistical fluctations we see in thermodynamics. As you can see in the values quoted in Table 1 the bond energies associated with the weaker types of bonds are comparable to thermal energy.

- 1

This is not referring to the Strong and Weak fundamental forces