2.1 Polymers: Types#

What are polymers?#

You are all already familiar with atoms and will have some insight into how small molecules behave, most likely from thermodynamics courses and the idea of degrees of freedom. These small molecules typically have a few atoms (think \(\text{H}_2\text{O}\), \(\text{CO}_2\) or \(\text{N}_2\)), whereas a polymer is a very large molecule that is comprised of a large number of repeating units or monomers1, and often interchange between the two words.

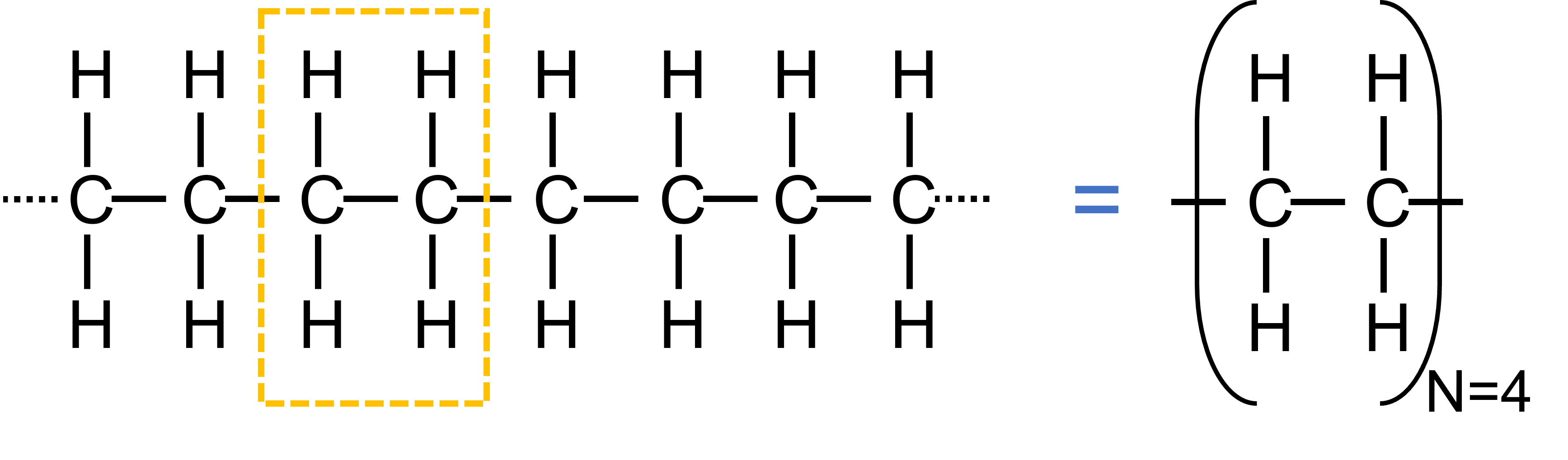

A key parameter when describing a polymer is \(N\), the degree of polymerisation. This is more of a chemistry definition so a simpler definition of \(N\) is the number of repeated units in the polymer chain. It is worth stressing here that the number of units in a chain is not the same as the number of atoms in a chain. For example in Fig. 16 we see a polythene chain with \(N=4\). One unit is an ethene monomer \(\text{CH}_2-\text{CH}_2\), indicated by the dashed box, and we have four of these units in the diagram.

Fig. 16 An example of a polythene oligomer, i.e. a very short chained polymer. The left hand side is a schematic of the full chain (ignore the dashed left and right bonds, as these would need terminating units) with a single monomer highlighted by an orange dashed box. The right hand side is the same molecule but in condensed / shorthand notation.#

Although I’ve chosen to draw a schematic with \(N=4\), in reality many polymers can have of order \(10^4\) units and sometimes even more. In terms of size a typical polymer will be around \(10\)’s of nanometers which seems rather small but compared to the atomic or diatomic molecule lengthscale it is rather large - two or three orders of magnitude larger than the Bohr radius, for those who like a numerical comparison.

The way that we define the size of a polymer is not as clear cut compared to atoms so we will spend some time later going into the detail of quantifying polymer sizes.

Fundamental principles of polymer structures#

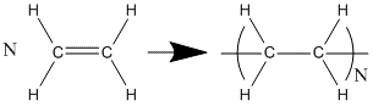

The most simple arrangement of these units is as a chain comprising of multiple identical units in a linear chain, known as a homopolymer. One of the most widely known homopolymers is polyethylene (often known as polythene), which is formed from ethylene monomers (Fig. 17).

Fig. 17 Polymerisation of \(N\) ethylene monomers into a polyethylene polymer with degree of polymerisation \(N\)#

Whilst a linear homopolymer is conceptually the simplest, it is far from the most practical. As the overall properties of a polymer material depend on the monomers used it is often beneficial to mix polymers with different properties to form a copolymer. For example the addition of acrylonitrile into a chain of styrene monomers gives a resulting copolymer that has greater thermal, mechanical, and chemical resistances compared to a polystyrene homopolymer ([Harper, 1999]).

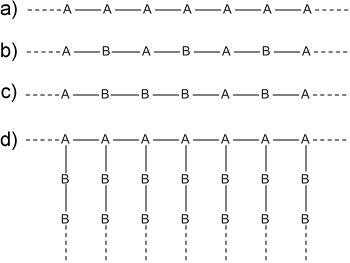

There are a variety of ways in which two (or more) monomer species can be integrated into a polymer structure. Fig. 18 shows a linear homopolymer (a), and two types of linear copolymers: (b) comprises of alternating monomers along the chain, whereas in (c) the monomers are randomly distributed along the chain. Of course polymers are not restricted to forming linear structures; if a monomer has the chemical structure to facilitate additional bonds then multiple chains or branches can form from these units. Chain (d) of Fig. 18 shows a grafted copolymer in which chains of B monomers are grafted onto a linear backbone of A monomers.

Fig. 18 Possible configurations of polymer chains; a) homopolymer, b) alternating copolymer, c) random copolymer, d) grafted copolymer.#

Furthermore, the orientation of the monomers is important when considering the properties of the polymer. Whilst this is not immediately clear when considering polymer structures in terms of A and B monomers, one can appreciate the importance from the grafted copolymer previously mentioned. Consider a grafted copolymer in which the side chains (that is, the -B-B- branches) terminate with a monomer that interacts strongly with another material. In the presence of this material such end monomers will prefer to interact with it and so the grafted copolymer will easily fix itself with the backbone (-A-A-) oriented away (much like a upright comb held teeth down). However if the side chains alternate between ‘above’ and ‘below’ the backbone there will be competition between the side chains to interact with the material.

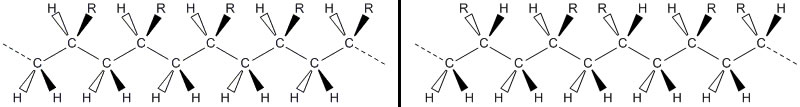

The orientation of the monomers within a chain is known as tacticity and is shown in Fig. 19. The tacticity of a polymer has great importance in the thermal properties (crystallisation and melting) [Paukkeri and Lehtinen, 1993], permeation of gas [Min and Paul, 2003], miscibility of polymer blends [Beaucage et al., 1991, Vorenkamp et al., 1985], as well as allowing the formation of previously unproducable polymers [Washburn et al., 2006].

Fig. 19 Molecular tacticity. Left shows an isotactic molecule in which all (generic) R groups are out of the page. The right hand image is a syndiotactic chain whereby the R group alternates between into and out of the page for each monomer. A third type (not shown) is atactic in which the orientation of the R groups is random.#

It is therefore important that not only the individual constituents of the polymer are known, but also the order, amount, and orientation of the monomer species that form the resulting chain.

Types of polymers#

There are three broad and not completely exclusive categories of polymers: plastics, semiconducting polymers, and biopolymers.

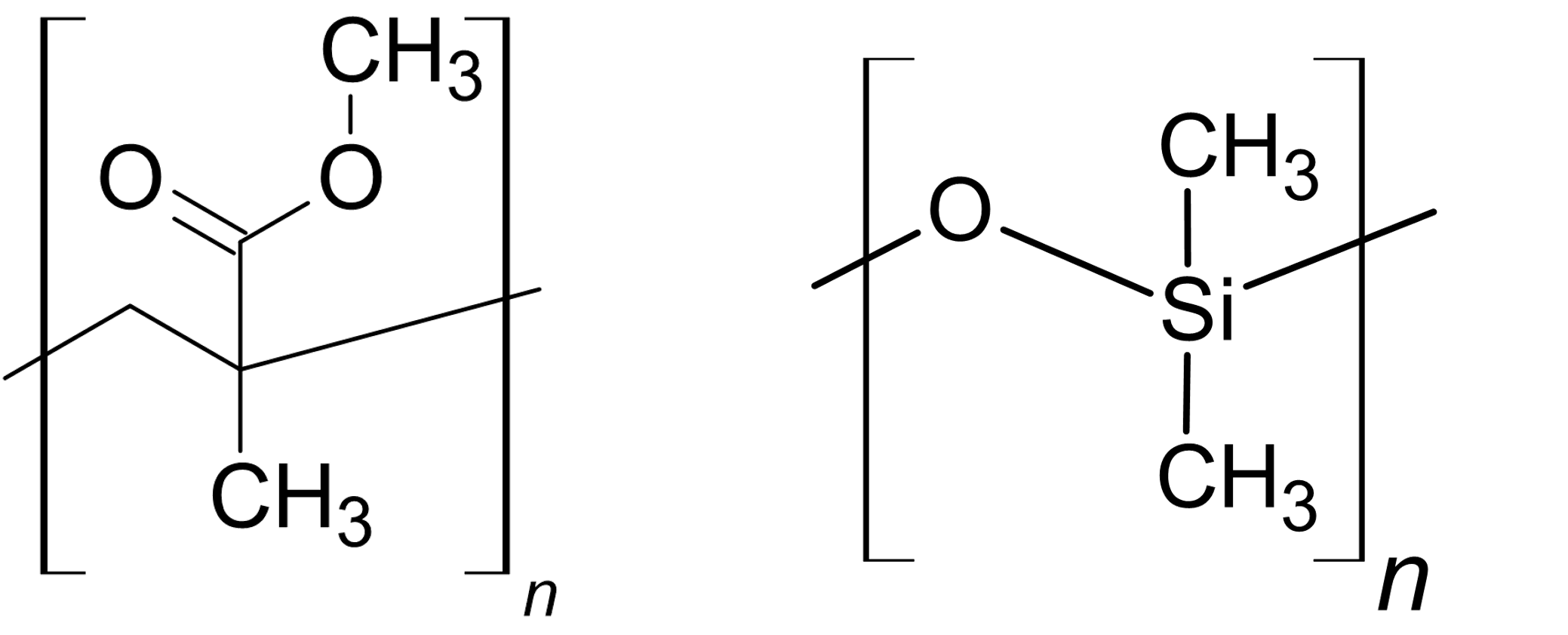

Plastic type polymers, such as those shown in Fig. 16 and Fig. 20, are generally the most simple in terms of their molecular structure. They often have a simple backbone and relatively simple side groups. Take PMMA in Fig. 20. The backbone is a the zig-zag chain of carbons and a relatively small side group ‘above’ the chain comprising of two oxygen atoms and a \(\text{CH}_3\) molecule. Despite being a relatively simple side chain these play an important role in the macroscopic properties we observe - in the case of PMMA it has a \(T_g\) of around \(383\text{ K}\) but adding an extra \(\text{CH}_2\) between the O and \(\text{CH}_3\) reduces \(T_g\) by approximately \(30\text{ K}\).2

And although many plastic type polymers are normally a long chain like polymer, by using some interesting chemistry you can change the overall topology of the molecule as we have already discussed in the previous section.

Fig. 20 Two example of plastic type polymers. On the left is poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA), often called perspex. On the right is poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS), often called silicone.#

Semiconducting polmyers are somewhat similar to plastic type polymers in that their structure tends to be a long chain molecule with some side groups, but the backbone is often more complex in modern semiconductor type polymers. In the earliest discovered semiconducting polymer the backbone was a carbon-carbon double bond but more efficient modern polymers use benzene or other aromatic rings as a chain. We will not be going into the detail around how semiconducting polymers work, but the short answer is that units along the main chain have conjugated bonds meaning that electrons become delocalised from a particular unit and can become charge carriers along the polymer. Adjusting the side chains can change and moderate the band gap associated with these conjugated bonds meaning, with some fancy chemistry, one can change the semiconductor structure akin to the hard crystalline type you have seen in your solids courses.

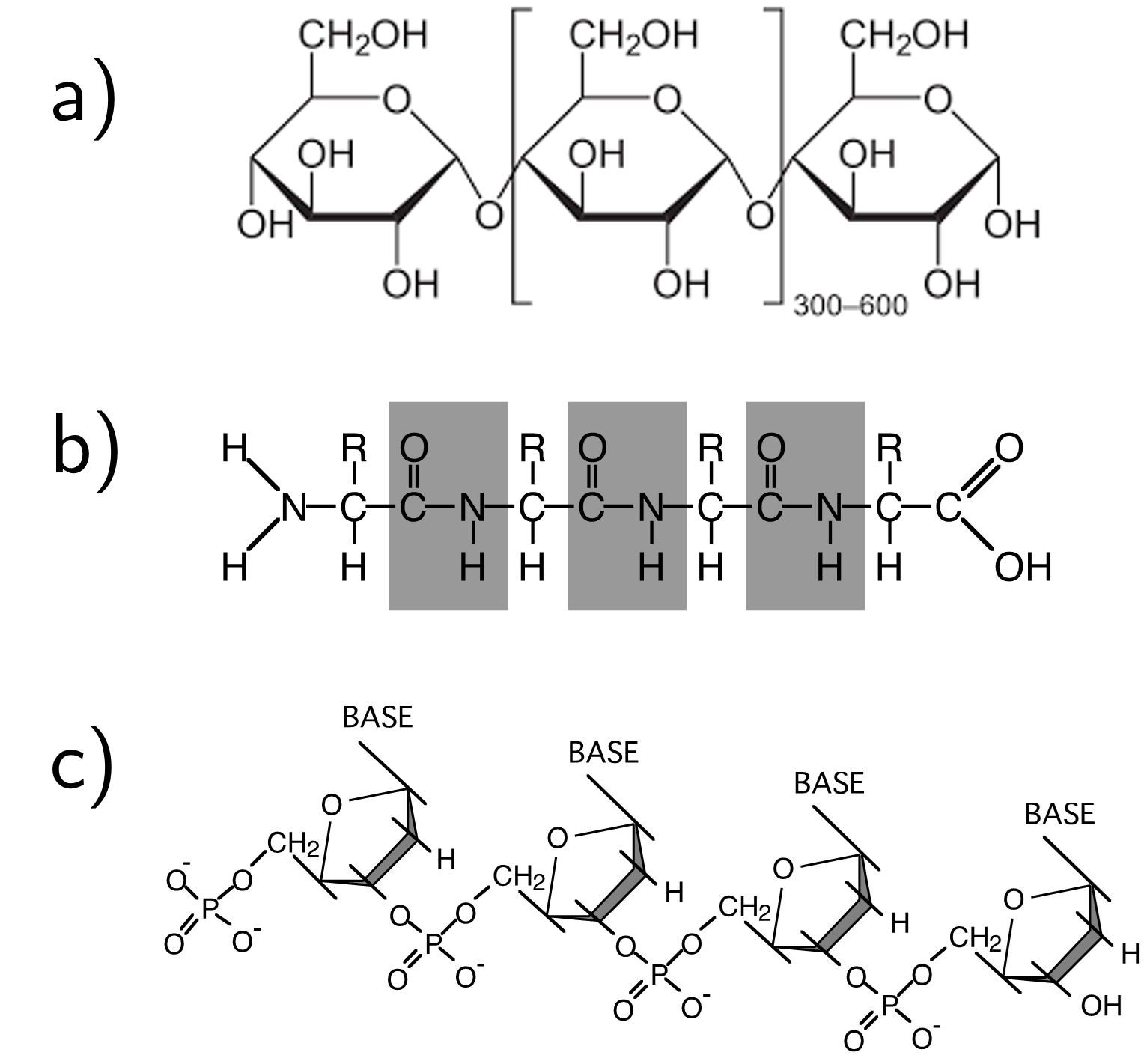

Finally we come to biopolymers. Despite these types of polymers often being composed of more complex molecules, the underlying structure still remains broadly the same. Some more simple biopolymers such as amylose (starch) are linear polymers formed from 300-600 repeat units, and other types such as proteins are linear copolymer chains with different functional side groups that gives rise to the functionality of the protein itself. Finally we have DNA which is another copolymer of alternating sugar and phosphate units, and the bases that make up the functionality of DNA are attached to these units. Even though DNA could be considered a random copolymer (as per Fig. 18), there is a global order to the molecule that dicates, well, everything about our biology. These three examples of biopolymers can be found in Fig. 21.

Fig. 21 Three examples of biopolymers; a) amylose, b) protein backbone with the function group R providing the functionality of the molecule, and c) DNA.#

Topology#

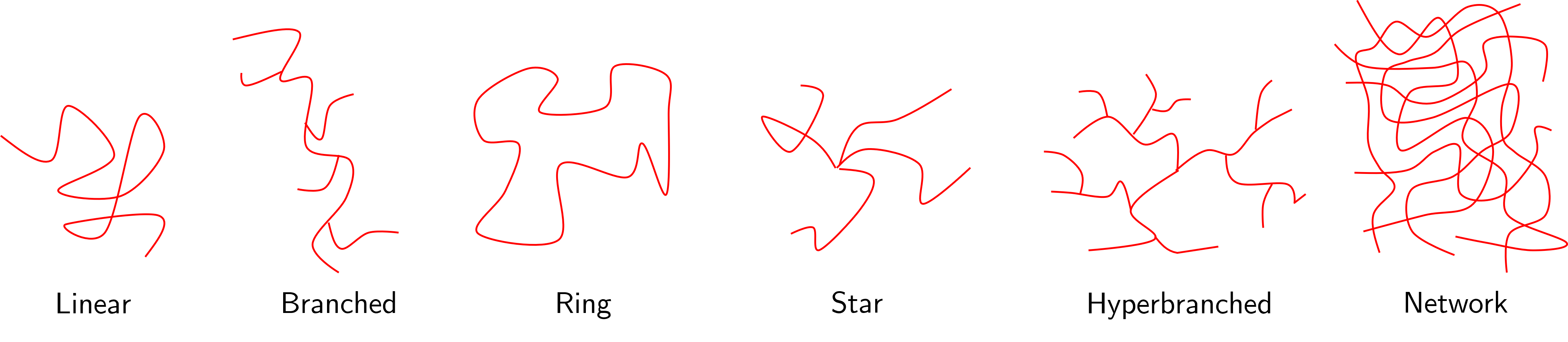

We are not going to spend much time and effort in understanding polymer topologies in great detail, but it is useful to be aware of the different types that exist as you may see them as part of your wider reading. Some rough sketch schematics of the more common topologies are shown in Fig. 22.

Previously we thought about polymers as being a long molecule comprised of a backbone, some of which have small side groups that introduce some functionality or property to the final material. It is possible to take this long linear molecules and join them together in a number of different ways. One may be that instead of having small side groups, there are other polymer chains joined to the main backbone (a branched polymer). Alternatively a polymer can join together with itself (ring) or ends from many polymers join at the centre of a star like structure.

Other systems that give rise to novel and sometime unexpected macroscopic properties are hyperbranched polymers (i.e. those with branches on branches, etc) and networks (effectively a tangle of polymer chains, although some order to the structure can be imposed with careful chemistry). These two systems allow for long range cooperativity if not completely regular order. Take networks for example - these systems are able to swell many many times their original volume by allowing solvent molecules to penetrate into the network and cause the chains to stretch without the network itself being broken. Each chain only needs to stretch by a small amount which can lead to substantial macroscopic swelling. The gels you find in nappies, sanitary towels and aqua beads are exactly these types of polymer networks and can swell by two or three orders of magnitude by absorbing water.

Fig. 22 Different topologies of polymer chains and systems.#

Polymer physics, not polymer chemistry#

I’ve been working with polymer systems since 2005 and one of the most frequent questions I get asked is whether I’m a chemist. I always answer this with my usual charm and tact. But it is actually a fairly sensible question given that in a lot of the previous sections I have shown you a whole bunch of chemistry diagrams and talked about carbon-carbon bonds and functional side groups.

This interest in what the polymers are made of, at the monomer and ‘within chain’ level, is what we would broadly classify as polymer chemistry. Polymer chemists bring expertise and understanding to how and why the different groups behave as they do, and the more experimental ones devise new and frankly astonishing chemical synthesis protocols to build the molecules that we need.

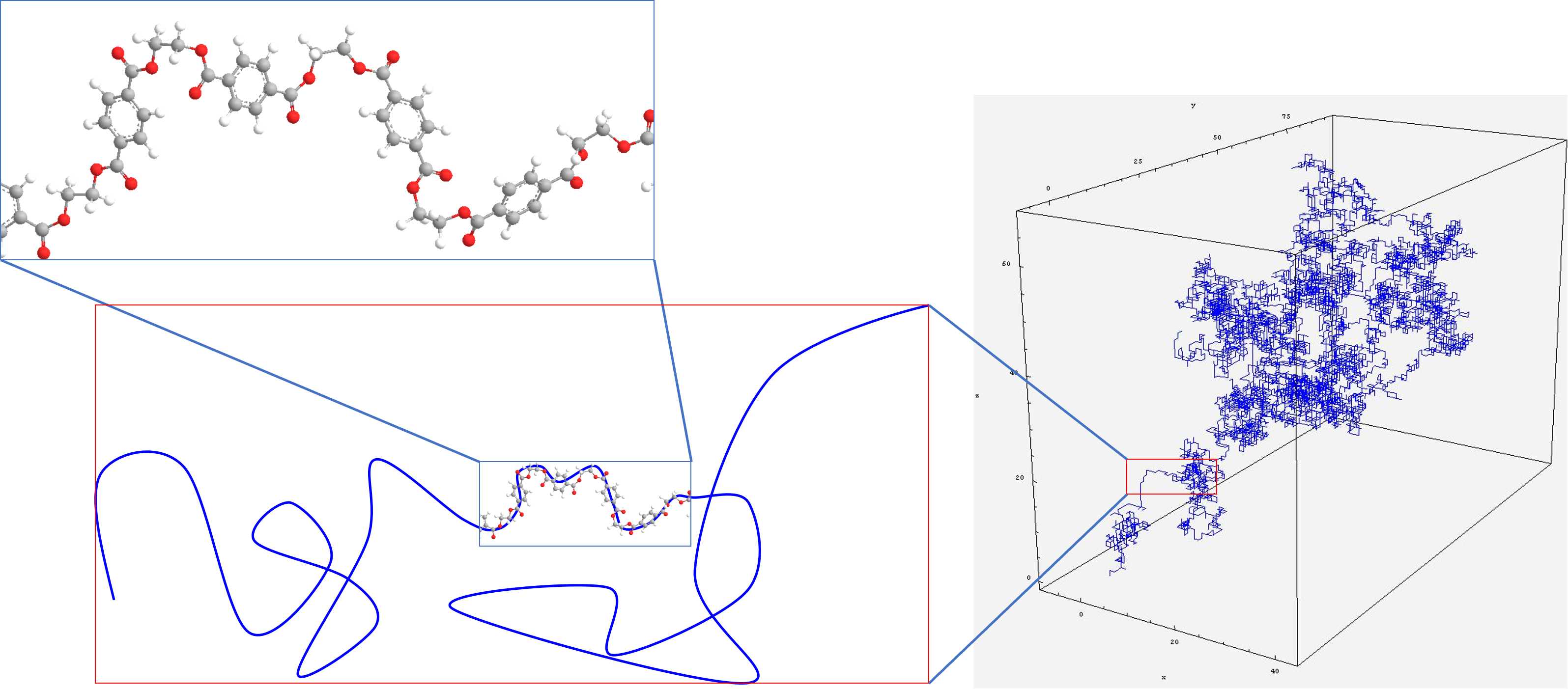

Fig. 23 Polymer chemists are interested in what makes up a polymer, whereas polymer physicists often simplify the system into a series of connected vectors or as a random walk system#

Polymer physicists on the other hand take a rather different perspective as shown in Fig. 23. Instead of thinking about what the chain is made of, we tend to step back and think about the chain as a 2- or 3-dimensional entity. We forget that the monomers are actual chemical structures and instead conceptualise them as either random walk systems, as vectors with mass or indeed a hybrid of the two. What is very surprising is how extremely accurate this approach is, as we will see in section on Ideal Chains where we use this random walk vector approach to predict the size of polymers, and compare this to experimental results.

Bibliography

- Har99

C. A. Harper, editor. Modern Plastics Handbook. McGraw-Hill, 1999.

- BeaucageSteinHashimotoHasegawa91

G. Beaucage, R. S. Stein, T. Hashimoto, and H. Hasegawa. Tacticity effects on polymer blend miscability. Macromolecules, 24(11):3443 – 3448, 1991.

- MinPaul03

K. E. Min and D. R. Paul. Effect of tacticity on permeation properties of poly(methyl methacrylate). J. Poly. Sci. B. Poly. Phys., 26(5):1021 – 1033, 2003.

- PaukkeriLehtinen93

R. Paukkeri and A. Lehtinen. Thermal behaviour of polypropylene fractions: 1. Influence of tacticity and molecular weight on crystallization and melting behaviour. Polymer, 34(19):4075 – 4082, 1993.

- VorenkamptBrinkeMeijer+85

E. J. Vorenkamp, G. ten Brinke, J. G. Meijer, H. Jager, and G. Challa. Influence of the tacticity of poly(methyl methacrylate) on the miscability with poly(vinyl chloride). Polymer, 26(11):1725 – 1732, 1985.

- WashburnLauterbachSnively06

S. Washburn, J. Lauterbach, and C. M. Snively. Polymerization of Unpolymerizable Molecules through Topological Control. Macromolecules, 39(24):8210 – 8212, 2006.

- 1

For anyone interested in etymology, the “-mer” means unit, so “mono” prefix means a single unit whereas “poly” means many. “Poly + mer” = “Many + units.”

- 2

This change in chemical structure actually changes it from PMMA to poly(ethyl methacrylate). If you add a couple more \(\text{CH}_2\) units you get poly(butyl methacrylate) with \(T_g\) around room temperature.