3.3 - Mechanisms of phase separation.#

There are two dominant mechanisms of phase separation. Which mechanism occurs depends on how we quench our system out of the stable one phase part of the phase diagram.

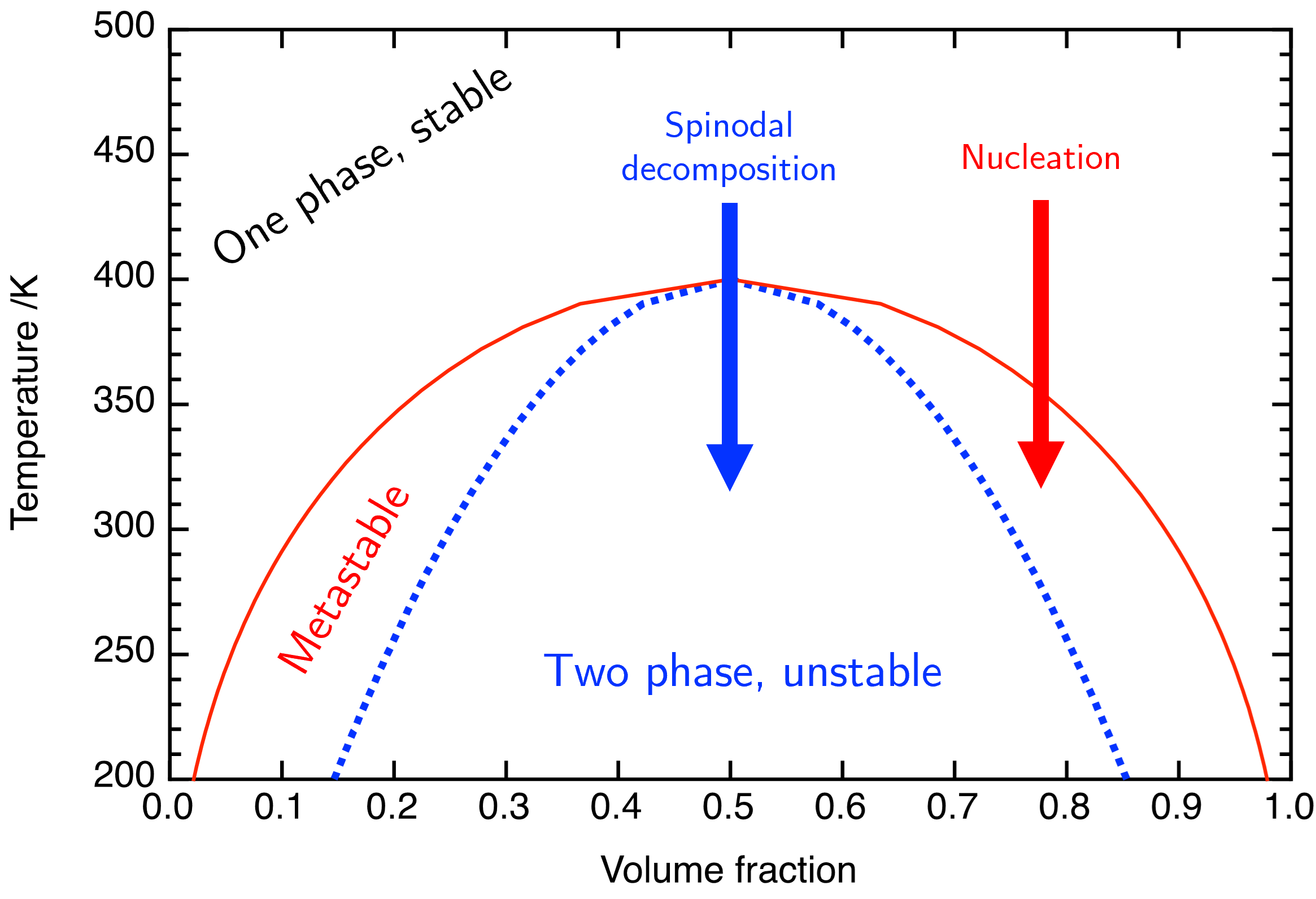

Fig. 50 A phase diagram for a simple molecular liquid-liquid system, this time expressed in terms of temparture rather than \(\chi\).#

Consider Fig. 50 in which I have changed \(\chi\) with \(T\) giving a reflection of the diagram seen previously. If we reduce the temperature such that our point moves from the stable to the unstable part below the spinodal line the phase separation mechanism is spinodal decomposition whereas moving from the stable to metastable will result in the nucleation mechanism. We’ll consider each of these in turn.

Spinodal decomposition#

Within the spinodal line any small local change in composition will lower the free energy (e.g. around \(\phi_B\) in Fig. 48). The system is unstable and any fluctuation in composition is amplified as material flows from regions of low concentration to high concentration1. This should strike you as a little odd to start with. For diffusing systems we expect the material to diffuse from high to low concentrations in order to reach a uniform concentration.

The answer is that it is not the concentration that needs to be uniform at equilibrium but the chemical potential. Material will flow down a gradient from high to low chemical potential. The chemical potential is related to \(\frac{\partial F}{\partial\phi}\), so if the second derivative of the free energy with respect to concentration is positive then the concentration will flow from high to low. But if the second derivative is negative, which is the definition of the spinodal region, then material will flow from regions of low to high concentration.

It may surprise you that these fluctuations have a characteristic lengthscale. You can find the rigorous proof elsewhere but we can rationalise a qualitative argument for why this lengthscale exists, which is all we need for this course.

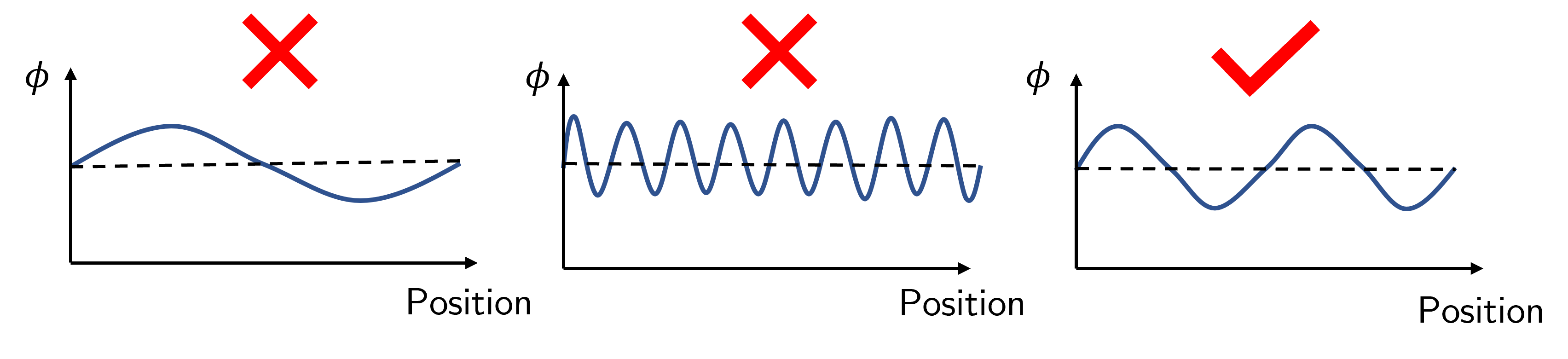

Fig. 51 Spinodal decomposition. Long wavelengths (left) are unfavourable as the time required for molecules to diffuse is too large, whereas small wavelengths (middle) introduce a high amount of interfacial energy. The intermediate wavelengths are just right.#

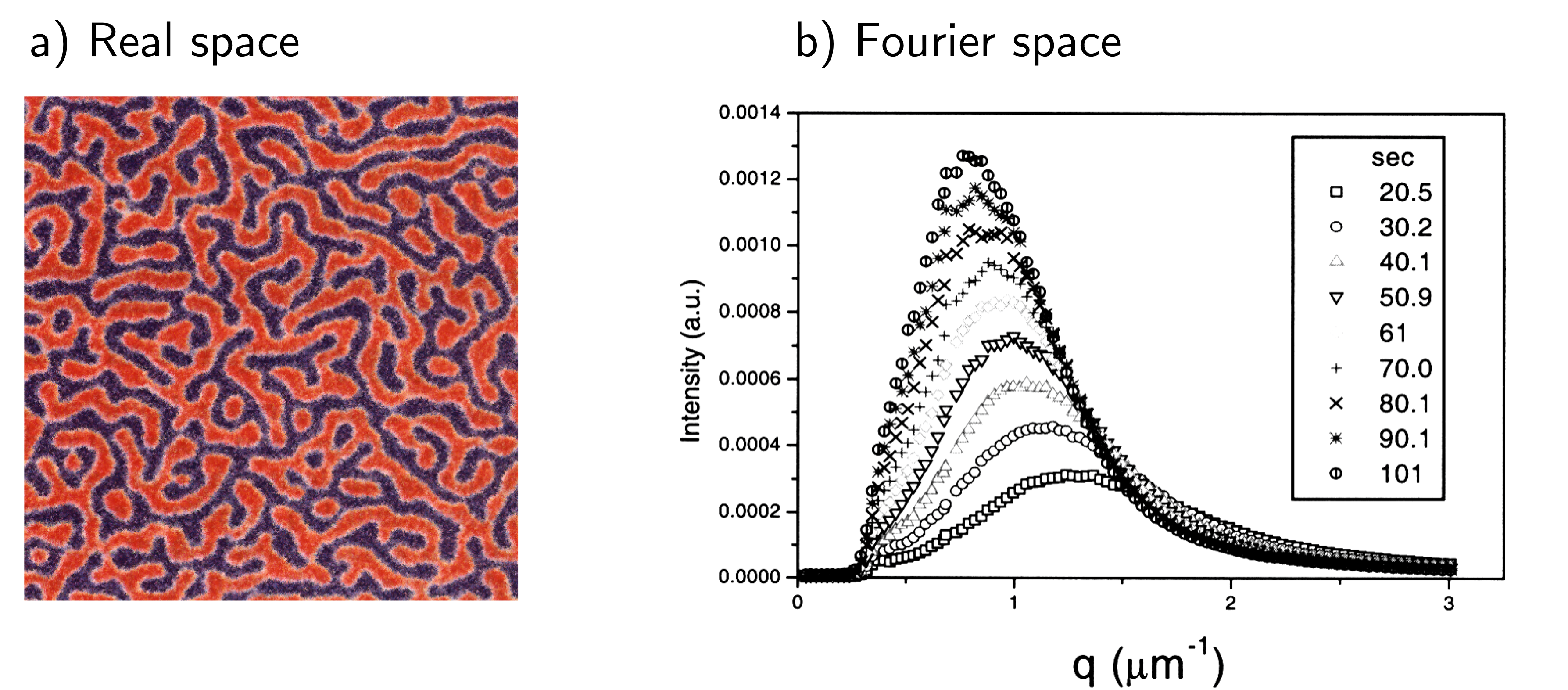

The longest lengthscales (i.e. the polymer A and polymer B rich flucturations are very large) are unlikely to occur because they require like molecules to diffuse over a large distance which is a slow process. Shorter lengthscales have a large amount of interface between the two polymer species, and interfaces require energy so having a large amount of interface is energetically unfavourable. Thus we expect a lengthscale that best balances the time requirement for polymers to diffuse into / out of the region and the energetic cost of interfaces. Fig. 52 shows an image of a polymer blend undergoing spinodal decomposition (left), and the characteristic inverse lengthscales from scattering experiments (right). Note that the lengthscales increase with time rather than remaining at one characteristic lengthscale

Fig. 52 Spinodal decomposition seen in real space (i.e. through a microscope) and in Fourier space (i.e. from scattering experiments). The Fourier space data allows us to determine a characteristic lengthscale of the spinodal structure.#

Nucleation#

Unlike spinodal decomposition that is the result of small local fluctuations, nucleation occurs in the region where any local fluctuations would increase the free energy (e.g. around \(\phi_A\) in Fig. 48). Instead we require a process that produces a large change in local composition that will reduce the free energy. For this to happen we require a particle to be nucleated by a thermal fluctuation.

Let us consider how much energy is required to nucleate a particle of size \(r\). Firstly there will be a negative contribution to the free energy proportional to the volume of the particle, \(\Delta F_V\) per unit volume. This decrease is because the mixture is initially globally unstable so complete phase separation in the particle will lower the free energy. Next the creation of a droplet requires the creation of an interface between the droplet and surrounding polymer. This interface has an interfacial energy \(\gamma\) per unit area and is a positive contribution to the free energy.

Bringing this all together the net change in free energy on nucleating a droplet of size \(r\) is

There exists a critical size \(r^*\) below which droplets are unstable and their growth would increase the free energy of the system. Droplets above \(r^*\) are stable and their growth would decrease the free energy.

This \(r^*\) can be found by finding the minimum in equation (56), namely

from which the energy required to create this critical nucleus can be found,

Nucleation is an activated process meaning it requires a fluctuation that increases the local free energy by \(\Delta F^*\), and the probability that this fluctuation is determined by a Boltzmann factor. Thus the rate at which nucleation occurs is proportional to \(\exp\left(-\frac{\Delta F^*}{k_\text{B}T}\right)\).

This is generally unlikely at everyday temperatures but in reality the barrier for nucleation to occur is greatly reduced at surfaces, barriers or when defects (dust, for example) are present to act as a seed for nucleation.

- 1

Low and high are in terms of `like’ polymers. So a region of high concentration for A means lots of A but little B, etc